As I always say, it is difficult to know what is actually going on in the world. Politicians, the media, academics and other so-called analysts, so-called "experts" in general, they all like to talk as though they know what is going on, but a lot of the time they don't, and even when they do they tend to tell the rest of us an edited (at best) or blatantly distorted (at worst) version of what is happening, with the intent of getting us to come to certain conclusions (i.e. the conclusions supportive of their agenda, whoever they happen to be).

There has been a lot of "low intensity" conflict in South Sudan since its separation from Sudan. Of course, no conflict is "low intensity" to the people who get killed, to the families left behind, or to the communities negatively impacted by whatever metric. The current political impasse may or may not lead to a bigger civil war (and one suspects outside players, regional and global, will bring pressure to bear on the key leaders to avoid open war), but it is likely that the state of low intensity conflict will continue.

In this, both Sudans are the same. The erstwhile "North" Sudan is also a place of constant, ceaseless, simmering conflict.

As a Nigerian, I am used to people who claim dividing a country will somehow solve the country or countries' problems. I have always wondered why people think that. It doesn't make any sense. If you divided Nigeria, each new piece will inherit every problem is already has ... and will also inherit the same useless political leaders that have already proven useless at solving the problems.

There is this tendency to point to the Czech and Slovakian republics as some sort of example. I am tempted to ponder whether the example is as great as is portrayed, but the fact of the matter is even if it were the most perfect example of separation ever recorded, it would still remain the case that both subsequent countries inherited status quo ante conditions from the preceding Czechoslovakia that are absent from other areas that are often portrayed as potential beneficiaries from the same outcomes.

Besides, the European continent is an odd place. Every few decades, there is a dramatic adjustment of internal borders that is hailed as a sign of great statesmanship, and is treated as though it were not only permanent but also a solution to all the problems that had existed before the realignment of borders. After some years, or some decades, there is another upheaval, whereupon borders change dramatically again. With all due respect, and meaning no offence to either country or to the citizens therein, but there is no particular reason to believe the Czech or Slovak republics will remain as they are indefinitely, or even that the future citizens of both countries will remember the separation fondly.

Heck, contrary to popular belief, the entity "Nigeria" as currently constituted might outlast the current European borders; as it stands, we have already outlasted the USSR, the GDR, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia. It seems Belgium is under stress, the Scottish National Party is flirting with a referendum, and one wonders if the much-ballyhooed European Union has more staying power than the Nigerian Federal Republic.

Look, I am not trying to offend anyone, but problems are problems. You either solve them or you don't. I am not overly fond of Felix Houphouet-Boigny's politics, but there is a statement credited to him (I don't know if he really said it) on the topic of uniting all former African colonies of France into one country. He asked whether they were all supposed to unite and share each other's poverty.

Uniting two poor countries won't make a rich one. Dividing a poor country will not create two rich ones. Dividing a violence-prone country creates two violence-prone countries. Dividing a lawless country creates two lawless countries. The Czech and Slovak republics did not become relatively wealthy because they were divided, and they would not have been relatively poor if they had stayed together.

That is all I am saying.

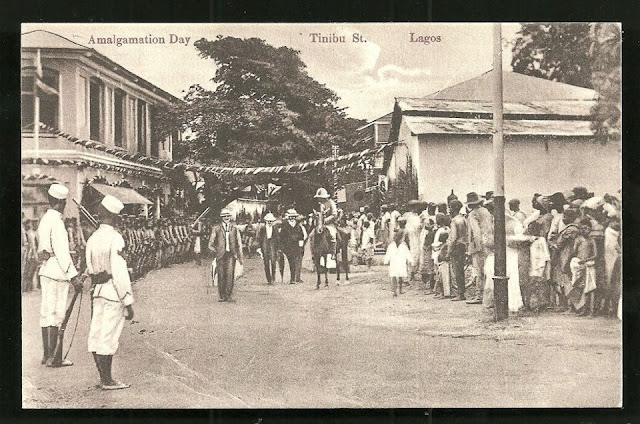

Amalgamation Day in Lagos, 1914

20 December, 2013

13 December, 2013

Continuing the focus on Fiscal health ....

If you haven't done so already, peruse this brief report from Business Day (Nigeria) on the fiscal implications of the 2014-2016 Medium Term Expenditure Framework.

10 December, 2013

Economic Statistics of the Nigerian States & Territories

I am not sure I trust our census results or any other "official" statistics. I don't just mean Nigerian government statistics, but the statistics produced by multilateral agencies, non-governmental organizations, academic researchers and even the mass media.

But you have to work with what you have.

Renaissance Capital did a report on the economies of Nigeria's 36 states and 1 Territory.

The Middle Eastern business site Zawya posted this table indicating some of the key findings of the Renaissance Report:

But you have to work with what you have.

Renaissance Capital did a report on the economies of Nigeria's 36 states and 1 Territory.

The Middle Eastern business site Zawya posted this table indicating some of the key findings of the Renaissance Report:

24 November, 2013

Still Talking About Nigerian Debt

Image from Ghana Business News

As you know, if you've been reading this blog (the stats tell me there are at least a few of you), I am not overly fond of the "debt cancellation deal" of 2005.

The future value of the $12 billion we paid was equal (at a minimal interest rate) to what our Paris Club creditors could have realistically expected to receive from us based on what we were actually paying at the time. The opportunity cost, or lost value to us, was much greater; those reserves could have been used to leverage even greater spending (greater than the reserves) on our infrastructure problems (or health problems, or education problems, or security problems, or etc), with economic effects in excess of the so-called billion-dollar-a-year savings.

And we were always bound to run up new debt, meaning we would resume paying the same amount (or more) in debt service that we were already paying, except with $12 billion less in our accounts. Indeed, in the years since the "debt cancellation" we have borrowed back about as much as we owed before the "cancellation", though nobody notices because it has been accumulated as "domestic debt" and not the more noticeable "Paris Club" debt.

The Federal Government's Debt Management Office says the Federal Government currently owes $45 billion in "domestic debt". Most of this was borrowed after the "debt cancellation" deal, and it is 50% higher than our "cancelled" external debt was in 2005. The DMO has data on the states' external debts, but if they have data on the domestic debt owed by the states, I haven't found it yet. Most articles I have found on the internet that rank state debt in Nigeria only reference each state's external (i.e. foreign) debts, and don't acknowledge that is another set of debts they are not reporting on. Like the federal government, the states' debts to Nigerian banks are likely much higher than their debts to foreign creditors.

The Vanguard columnist who writes under the pseudonym "Les Leba" has a tendency of pointing out that the debts are the result of our governments depositing oil revenues in Nigerian banks, and then borrowing back the government deposits as loans from the Nigerian banks at double-digit interest rates. It isn't a new concept; the African continent's historic Paris Club debts were for all intents and purpose a function of African countries depositing their foreign reserves and export revenues in Paris Club countries and then borrowing back their own money from the foreign countries with interest tacked on. The term "Paris Club" is apt, considering the fiscal and debt relationships between France and the CFA Zone are especially weird.

We tend to keep our eyes on the Federal Government when it comes to issues of debt. Nevertheless, the 36 State Governments and the Federal Capital Territory are also borrowing, and it seems no one is paying attention. There has been no legislative, political or democratic limitation to the borrowing of the states since 1999; our state governors (and the FCT minister) are far more powerful, relatively speaking, within their respective "domains" than the President is over Nigeria.

I am unaware of any independent, credible studies of the sustainability of the growing debt loads of the states. There are a few states where one suspects debt loads have passed the point of "comfort"; I have had interesting conversations with people who have praised their state governors for spending on certain projects, while simultaneously telling me they doubt their states can pay the contractors or the banks that funded the projects.

Truth be told, the state governors are in office a maximum of 8 years, winning re-election in part by rigging and in part by popularity bought with the debt, after which they leave office as wealthy men and leave the state's debt for their successor(s) to deal with. What do they care?

Debt is unavoidable for governments, corporations and individuals. It is not necessarily or inherently a bad thing. But there are questions to be asked and answered. One of the most important questions relating to our 36+1 states is whether each individual state's ability to repay its debts. When the civil service minimum wage was increased by the Federal Government, most state governments protested their inability to pay; clearly their margin for new expenditures is thin to the degree of nonexistence. Yet their debts, and (by definition) their annual fiscal commitments to pay those debts, will continue to grow, eating and exceeding that nonexistent margin.

There are other questions, like what is this debt being used to do? There are lots of things that either look nice, or feel nice, but which don't generate revenue sufficient to pay for their creation or for their maintenance. Many Local Government Areas and States have nice new medical facility buildings but cannot not afford to properly staff, equip or resource the buildings to a degree that would have a real impact on the health of the respective communities. And as they commit ever more of their budgets to paying debts, they will have even less in the way of discretionary resources.

Speaking of which, as I said earlier, Nigeria at the Federal level has borrowed back as much in new debts as we used to owe before the "cancellation" deal. Much of this debt was not used for anything relevant to economic growth or citizen welfare. There was a particularly large jump in the debt in the run-up to the 2011 Elections; effectively Nigerian citizens have to (re)pay the political/electoral expenses of the Jonathan Administration and the Peoples Democratic Party.

The debt situation is about to get worse, though the statistics will show that it has gotten better.

Let me explain.

Nigeria's Gross Domestic Product is currently being recalculated via "rebasing". It has been almost 25 years since we last rebased the GDP calculation, and the expectation is we will either overtake South Africa and become the biggest economy in Africa, or will dramatically shorten the amount of time before we overtake them.

The new, much higher GDP figure will cause all of our macroeconomic ratios to change. It will mean the various governments' tax collections will be a smaller total share of the economy. It will mean the various governments' total deficits will be a smaller share of the total economy. It will mean the debt-to-GDP ratio will drop. It will also mean the number used to represent the estimated growth rate of the economy will change from the 6-to-7% range to the 3.5-to-5% range.

To make a long story short, the three tiers of government are likely to use the rebased GDP size as a justification to increase their borrowing. One of the most annoying (to me) terms used by so-called experts (foreign and local) in relationship to Nigeria is "under-borrowed". They seem to think there is a specific amount of debt, relative to GDP, that we are supposed to be carrying, and if we are not carrying that amount of debt, they insist that we borrow a bunch of money for no reason at all beyond their insistence that we need to owe as much as they think we are supposed to owe.

We should owe only as much as is necessary. If the necessary amount of debt is less than what the experts claim it should be, then ... so what?

And even if there is a necessity, an indisputable need to borrow for a particular thing, perhaps the first question we Nigerian citizens should ask ourselves is what type of governments, government leaders and civil service bureaucracies we want to be in charge of this borrowing. Because, if we maintain the current system, we run the risk of having, for example, an $80 billion need in an infrastructure sector, for which our governments borrow $165 billion, and mysteriously deliver only $20 billion of new infrastructure that is useless without the other $60 billion's worth of completion, and now we the citizens owe $165 billion in addition to capitalized interest in exchange for a situation that is not demonstrably different from the situation that existed before we borrowed.

There is also going to be a lot of talk about increasing government revenues from taxation and fees. Some of this talk will be in terms of relieving the need to borrow. Some of it will be in terms of raising funds to pay back loans already borrowed and loans to be borrowed.

There are two sides to this coin. Whatever the real GDP of Nigeria is (I am not sure anyone really knows, rebased or otherwise), the citizens of Nigeria have long borne the fiscal costs of providing for themselves many of the things that are theoretically supposed to be provided by the public or private sectors of the economy. Assuming the government can efficiently tax the people so as to increase government revenue and decrease the discretionary revenue of private citizens, is there not a chance that the private citizen will be less able to provide himself and his extended family with those goods/services without there being a replacement of those goods/services from the government (i.e. paid for from the increased taxes)? Suppose the money just goes to pay debt? Suppose the money pays for more PDP election "victories"? Suppose the money goes to the right place, but $165 billion of spending in the right place mysteriously purchases only $20 billion worth of the whatever it is?

I am not being cynical (though I am sometimes a cynic). These are the kind of debates we should be having in our political space, rather than arguing with ourselves which of the "geopolitical zones" deserves the next "turn".

We have borrowed a lot of money. We are going to borrow a lot more, it seems. There needs to be more of a discussion about this ... before someone starts telling us it is a great idea to spend $24 billion to "cancel" $60 billion, only to borrow another $70 billion eight years afterwards.

02 October, 2013

Femi Aribisala on "Bigmanism"

If you haven't already, take a look at this funny essay in yesterday's Vanguard.

"Independence" Day 2013

Another year since 1960.

The big anniversary comes up in three months -- the Amalgamation Centennial on the 1st of January 2014.

I wish the Centennial was occurring in a different, better set of circumstances. As it stands, I suspect critical comments as to whether the Amalgamation was a good thing or not will predominate over celebratory comments.

The three tiers of government will probably put on glitzy shows, that will be more about expensive (as in contract-generating) excess. As per usual there will not really be anything that grabs at the heart and soul of who we are and why we are, nothing that really expresses our cultures or identities as distinct peoples or as a unified Federal Republic.

The big anniversary comes up in three months -- the Amalgamation Centennial on the 1st of January 2014.

I wish the Centennial was occurring in a different, better set of circumstances. As it stands, I suspect critical comments as to whether the Amalgamation was a good thing or not will predominate over celebratory comments.

The three tiers of government will probably put on glitzy shows, that will be more about expensive (as in contract-generating) excess. As per usual there will not really be anything that grabs at the heart and soul of who we are and why we are, nothing that really expresses our cultures or identities as distinct peoples or as a unified Federal Republic.

30 September, 2013

How we write about ourselves.

I promise you I decided to write this post before the recent tragic events at the College of Agriculture, Gujba in Yobe State.

Two things I have said often on this blog.

(a) The Fourth Republic is probably the single most corrupt period of our history so far; and

(b) The Fourth Republic is the second-most violent period in our recent history, behind only the Civil War. The First Republic would be third on the list of violent periods, despite the fact that many seem to look at it as though it were some sort of golden age of peace and prosperity.

There is enough violence going on that I would probably have had to apologize regardless of when I eventually wrote the post. But for the record, I was going to write this before what happened in Yobe.

But firstly, may the souls of the victims Rest in Peace. I don't know what else to say. There is nothing I can do to help.

I wanted to write a post about the way our media covers murder and mass murder, specifically the tendency to show graphic pictures of the victims.

Elsewhere in the world, they spare the families of the

deceased the shocking sight of their loved ones in the aftermath of something

like this .... whereas in Nigeria, the victims' bodies are

displayed without blurring, censoring or respectfully-placed pixels.

By the way, those media outlets from elsewhere in the world do not extend that level of respect to us when covering incidents of mass violence on our continent. For example, some years ago, on a weekend morning (i.e. when children were likely to be home), one of the USA's basic cable networks ran a documentary on Liberia and Sierra Leone, and showed everything, including one man's head which had been detached from his body and placed on a table. Had he been an American victim of a crime in the USA, either (a) they wouldn't have shown the head; or (b) they would have blurred his eyes so we the viewers (and particularly his family) would not .... see him. In fact, I think their channels are afraid of being sued by the families of American victims, but fear no consequence from us.

Still, how can we demand respect from other people when we do not respect ourselves? Reminds me of a speech I gave on Nigeria, where I instructed the audience to stop referring to Africa's (ethnic) nations as "tribes". After talking about this, that and the other, I took my seat and prepared to listen to the Kenyan who was due to speak next about Kenya. To my dismay, he spent the entire time referring to every single ethnic group in Kenya, one after the other, as a "tribe". It was a small enough group that I could see the people in the audience looking at each other in confusion.

By the way, I am not squeamish and this post is not about squeamishness. There is a time and place to look at and see the ugly realities of human history, of the human present and (unfortunately) of the human future. In the time and the place, I do not turn away.

That isn't what our media is doing, though. In fact, as you know, I am generally critical of how our media cover mass murders and single-victim murders. Their coverage of "communal violence" does very little to give us factual information about what actually happened, why it happened, and who actually did it. Their coverage of "communal violence" on the contrary tends to serve a fuel-on-the-fire role of sustaining the exact sort of cloud of misinformation that makes "communal violence" both likely and recurrent.

There are analysts and commentators who talk about something called "disaster porn". I wish they had chosen a different name for it (and shudder to think that some people will stumble onto this page after doing a web-search for something else). You can do a web-search yourself to find essays on "disaster porn" ... and when you've done that, consider that I think what the Nigerian media does is 100% "disaster porn" and 0% information.

More importantly they show 0% sensitivity in not even considering the fact that someone's mother, or father or spouse or child might opt to find out what happened in the world today, and find themselves looking unexpectedly at the graphic image of their murdered relative. You tend to hear police in certain countries talk about not revealing the names of the victims to the media until after their families have been informed -- in Nigeria, particularly now in the era of the internet, the pictures of the dead are posted even before the police know how many dead people there are, much less the names of family members to notify.

Do we even notify the families? A friend of mine, my next-door neighbour growing up, was murdered on the campus of one of our universities back when "cult violence" was rampant. His body was unceremoniously dumped with a pile of other bodies collected that night, and his parents had no idea what had happened because no one (not the police, not the university, no one at all) told them anything. After they hadn't heard from him in a long while, they travelled to the university, presuming to ask him what was going on .... only to be directed to the morgue, where they found him in a pile of other bodies.

That particular incident didn't make the news, because it was didn't met the threshold to count as good "disaster porn". There is a lot of stuff, violent stuff that happens in our Federal Republic that no one ever hears about, because there isn't an "angle" to it, no existing strings the news can be used to pull.

But that isn't really what this post is about.

There is a time and place for graphic images of violence and disaster. And there is a time and place when images can be presented, but should be "censored" to show sensitivity to the families of the victims.

There is also a philosophical principle involved in sensitizing people to something by showing them what it is without editing. But there is also a dangerous result where people see something so often they become inured to it (indeed, seeing incredibly graphic images of mass murder does not seem to lead to protests or outrage about the media showing us such images; on the contrary, we don't seem to react to it at all).

I wish someone would speak to the Nigerian media, and explain to them the difference. Unlike our politicians, I think the media is capable of learning.

May the souls of the victims Rest in Peace.

16 September, 2013

Quick Stats on Nigerian and South African Banks

I am posting this for the statistical content, and not in support of the viewpoint being expressed by its author via Business Day.

While I am on the topic of Business Day, there were a few months there where the quality of their sites and their journalism mysteriously weakened. But they appear to be returning to form as a, if not the, leading business publication in the Federal Republic.

I do think they need a little less coverage of random foreign business news culled from foreign news outlets, and a little more coverage of Nigerian business specifics. Seriously though, is the GDP in Jigawa or Taraba growing or shrinking? Farm output in Benue or Yobe going up or down? River transporation demand in Bayelsa going up or down?

Yeah, I know, it is easy for me to talk.

Anyway, I don't agree with the point that there should be fewer banks in Nigeria. What we need are stronger banks, regardless of the number. Soludo's consolidation of banks did little or nothing to affect the governance problems (among other problems) at our banks; it didn't help that Soludo's CBN was extremely lax in oversight and enforcement of the rules, partly by choice and partly because the banking grandees were untouchables, members of the PDP and supporters (funders) of President Obasanjo.

Philosophizing and ideologizing are neither here nor there in the practical world of economics, but it always bothered me that Soludo's idea of compelling Nigeria to have banks the size of South Africa consisted of dividing the same-sized pie among fewer banks, rather than increasing the size of the pie and the size of each banks' slice as a result.

I know we are a lot poorer than Japan, South Korea, Germany, France and the United Kingdom, but there is no fundamental reason why this should be the case. Sure, there is a lot of literature from a lot of people who purport to explain the discrepancy, but much of that (if not all of it) suffers from the same ailment that affects writings on history. In terms of this blog (and this blog post), the important thing to say is what I have already said: There is no fundamental reason why the Federal Republic of Nigeria should be poorer than the aforementioned. Whatever you assert to be the cause for this state of affairs is by definition something that can be corrected (and that should have been corrected a long time ago). We should plan our banking sector based on achieving that aim, as opposed to aiming at a destination (South Africa's economy) that is actually (with due respect) smaller than what we should be aiming for.

Besides, there are reasons why the South African banking industry is an oligopoly, and those reasons have nothing to do with free market determinism. In fact, one might be tempted to argue that the banking oligopoly is as problematic to the South Africa's long-term economic (and political) future as the oligopoly in land ownership and commercial agriculture.

You know what I mean.

Feel free to disagree with me. Nigerian politics would be a lot more relevant to Nigerian development if we engaged in serious debates about the banking industry, rather than asking ourselves which geopolitical zone, senatorial zone or other zone has the next chance in the rotation to produce the executive or legislator.

Anyway, here is the statistical diagram, courtesy of Business Day. You might have to click on it to see the full thing:

While I am on the topic of Business Day, there were a few months there where the quality of their sites and their journalism mysteriously weakened. But they appear to be returning to form as a, if not the, leading business publication in the Federal Republic.

I do think they need a little less coverage of random foreign business news culled from foreign news outlets, and a little more coverage of Nigerian business specifics. Seriously though, is the GDP in Jigawa or Taraba growing or shrinking? Farm output in Benue or Yobe going up or down? River transporation demand in Bayelsa going up or down?

Yeah, I know, it is easy for me to talk.

Anyway, I don't agree with the point that there should be fewer banks in Nigeria. What we need are stronger banks, regardless of the number. Soludo's consolidation of banks did little or nothing to affect the governance problems (among other problems) at our banks; it didn't help that Soludo's CBN was extremely lax in oversight and enforcement of the rules, partly by choice and partly because the banking grandees were untouchables, members of the PDP and supporters (funders) of President Obasanjo.

Philosophizing and ideologizing are neither here nor there in the practical world of economics, but it always bothered me that Soludo's idea of compelling Nigeria to have banks the size of South Africa consisted of dividing the same-sized pie among fewer banks, rather than increasing the size of the pie and the size of each banks' slice as a result.

I know we are a lot poorer than Japan, South Korea, Germany, France and the United Kingdom, but there is no fundamental reason why this should be the case. Sure, there is a lot of literature from a lot of people who purport to explain the discrepancy, but much of that (if not all of it) suffers from the same ailment that affects writings on history. In terms of this blog (and this blog post), the important thing to say is what I have already said: There is no fundamental reason why the Federal Republic of Nigeria should be poorer than the aforementioned. Whatever you assert to be the cause for this state of affairs is by definition something that can be corrected (and that should have been corrected a long time ago). We should plan our banking sector based on achieving that aim, as opposed to aiming at a destination (South Africa's economy) that is actually (with due respect) smaller than what we should be aiming for.

Besides, there are reasons why the South African banking industry is an oligopoly, and those reasons have nothing to do with free market determinism. In fact, one might be tempted to argue that the banking oligopoly is as problematic to the South Africa's long-term economic (and political) future as the oligopoly in land ownership and commercial agriculture.

You know what I mean.

Feel free to disagree with me. Nigerian politics would be a lot more relevant to Nigerian development if we engaged in serious debates about the banking industry, rather than asking ourselves which geopolitical zone, senatorial zone or other zone has the next chance in the rotation to produce the executive or legislator.

Anyway, here is the statistical diagram, courtesy of Business Day. You might have to click on it to see the full thing:

The Stories We Should Tell Louder

Back in

2010, a semi-acquaintance of mine attended a panel discussion on Nigeria

that was held in London sometime in 2010. This is an edited excerpt of

what he wrote about the event:

Father Matthew Hassan Kukah, and indigene of Kaduna State, was subsequently named Bishop of Sokoto in 2012. Before Jos in Plateau State took over as city most frequently mentioned in the context of "communal violence", Kaduna City, capital of Kaduna State, held that infamous position.

Father Kukah is one of many prominent Nigerian religious and sociocultural leaders who work very hard to end the scourge of communal violence. The story he told of the closeness between regular Muslims and Christians (his sister and her elderly neighbour) is one that deserved wider attention in the Federal Republic. The story he told of the senselessness of ultimately self-defeating nature of the violence should also have found a wider audience in Nigeria.

But nobody knows about it. The nature of the discourse in Nigeria is to loudly trumpet any and all news (even if unconfirmed) that contributes to sustaining the state of oft-violent distrust, division and dysfunction, and to downplay and minimize anything that would or could create a rallying point for the super-majority of Nigerians who would work to end the dysfunction if only there was an available route towards doing so.

We Nigerians (and Africans) often complain that the foreign media tends to highlight negative news about Africa, and to downplay positive news. We argue that the relentless negativity contributes to the sustenance of the the conditions that create the negative outcomes.

But we ourselves tend to highlight the negative about ourselves, and about each other.

I am not talking about criticism, constructive or otherwise. The only way anything can improve is to realize what about ourselves needs improvement ... but that implicitly acknowledges that we are able to improve. The problem with the negativity is that it is built on the notion that ... the best way to explain it is to revert, once again, to what we easily understand, non-African racism towards Black Africans. The racist theory that Black people are inferior presupposes that we cannot possibly be as good as anyone else, that we are automatically and irredeemably .... fill in the blank with negatives.

When certain Nigerians tout the division of the country as the "only solution" to our problems, or when people say that the Amalgamation was the source of all of our problems, there is an inherent belief that it is not possible to live in the same country with the other Nigerians, that it is not possible for us to live with them in the same country. Because they are just inherently and irredeemably ... fill in the blank with negatives.

I have had conversations with people where they start out agreeing with me in terms of critiquing the problems, but somewhere along the line, while I am still trying to analyze how we can all come together to solve the problem, the other person(s) branch off toward blaming another ethnic nation, geographical region, "geopolitical zone", or even senatorial zone for the problems. Even within a single town or city, the finger gets pointed at a socioculturally distinct neighbour (Ife and Modakeke, Aguleri and Umuleri, K-dere and B-dere, Zangon and Kataf), who is somehow to blame for the lack of jobs, the scarcity of land, and any other problems.

I know from experience that if you push through and continue arguing your case, those person(s) you are discussing with swing back from the knee-jerk response of blaming some other sociocultural group, and rejoin your analysis of what we could do together to fix the problem. However, the end of the conversation invariably involves both you and them concluding that it is unlikely that the problem will be solved in the real world.

As I've asserted in prior posts, this sort of negative political reaction to each other is the product of a sea of information in which we all swim.

Negativity, Violence and Shock Value sell newspapers and keep eyes attached to television sets. But while this is true of the commercial media everywhere, the overall nature of the discourse in most of the world's successful countries is to magnify and trumpet the best part of their national soul, and to sweep the less honourable parts of their national history under the carpet. Even what purports, in this age of political correctness, to be a less patriotic and hagiographic version of their history still rather underplays much of less edifying parts of their past; and much of what is presented as the "progress" of the present could be interpreted rather differently if one took a less rose-tinted view of events.

We do the opposite. We bury the best parts of our Federal Republic's shared soul, and overplay the worst parts of us. We not only treat the violent fringe as if it were the "normal" Nigeria, but go out of our way from an institutional and governmental point of view to facilitate the actions of the violent fringe as though we are not supposed to be otherwise, or rather cannot be otherwise. That is it right there. The idea that this, the violence, is who we are, and that it is not possible not to be this way.

But I didn't have to hear Father Kukah's story to know that the truth of Nigeria is quite different. In fact, while incidents of mass violence are rightly given wide coverage in the news, at any given point in time, most of Nigeria and Nigerians are not in fact subject to any violence.

Father Kukah's statement about violence and reprisal violence in the City of Kaduna, reminded me of a television report about two men who had previously been leaders of rival gangs of "youths" in Kaduna, gangs that attacked neighbourhoods of people from the sociocultural group of the rival gang (similar to what has been happening in the City of Jos since 1999). It was one of the few reports I had seen that didn't portray the violence as being one-sided.

These gangs are made up of youths who are unemployed, poor and prone to inducement by political factions. Indeed, a lot of violence in Nigeria is carried out by starving boys and youths who loot the homes and businesses of wealthier "foreigners" (i.e. non-indigenes). One of the more unfortunate aspects of our shared human history repeats itself: when poverty and economic uncertainty rise in any country (even in those so sure of their supposed "enlightenment"), the tendency is for gangs of poor, unemployed youths to see wealthy "foreigners" as having taken opportunities that should have gone to locals.

Of course, if we looked at it this way, we would have been obliged to fix the economic problems of our cities. But now that we just conclude it is ethnic or religious violence, we can throw up our hands and say there is nothing we can do about it.

What really struck me about the story is the two former gang leaders working together to end the violence in the city is how little coverage they received in the Nigerian media. They should be household names, but I only learned of them briefly and only from a foreign media source, not the Nigerian media.

It is time we gave greater prominence to stories of the good people, at least enough so that our people know there is another side to the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Here are links to previous posts I have made about stories that we should tell louder:

THE STORIES WE IGNORE An excellent feature by Tadaferua Ujorha for Daily Trust.

FIGHTING FOR PEACE An excerpt from a Weekly Trust essay by Carmen McCain about an old man who died doing the right thing, but who has been forgotten while we glorify and give national honours to the men and women responsible for creating the situation that killed this good man.

WE STAND TOGETHER Three articles.

GOOD DEEDS IN CENTRAL NIGERIA Self-explanatory (I hope the embedded links are still live).

The place was full to the brim and the debate was vigorous. The debate was about whether Nigeria was an African superpower and how an area that was able to produce incredible works of art like the Ife sculptures could end up the way it is today.

The panel included Father Kukah, who had interesting stories to tell about the religious conflict in Kaduna. One was about his sister who had a shop and was close to an elderly Muslim neighbour. When Christians were about to be attacked, the old man asked her to hide all her goods in his house. So when her shop got burnt down, she didn't lose much. But then the Muslim's house got burnt down in a revenge attack by "Christians" and she lost everything.

Father Matthew Hassan Kukah, and indigene of Kaduna State, was subsequently named Bishop of Sokoto in 2012. Before Jos in Plateau State took over as city most frequently mentioned in the context of "communal violence", Kaduna City, capital of Kaduna State, held that infamous position.

Father Kukah is one of many prominent Nigerian religious and sociocultural leaders who work very hard to end the scourge of communal violence. The story he told of the closeness between regular Muslims and Christians (his sister and her elderly neighbour) is one that deserved wider attention in the Federal Republic. The story he told of the senselessness of ultimately self-defeating nature of the violence should also have found a wider audience in Nigeria.

But nobody knows about it. The nature of the discourse in Nigeria is to loudly trumpet any and all news (even if unconfirmed) that contributes to sustaining the state of oft-violent distrust, division and dysfunction, and to downplay and minimize anything that would or could create a rallying point for the super-majority of Nigerians who would work to end the dysfunction if only there was an available route towards doing so.

We Nigerians (and Africans) often complain that the foreign media tends to highlight negative news about Africa, and to downplay positive news. We argue that the relentless negativity contributes to the sustenance of the the conditions that create the negative outcomes.

But we ourselves tend to highlight the negative about ourselves, and about each other.

I am not talking about criticism, constructive or otherwise. The only way anything can improve is to realize what about ourselves needs improvement ... but that implicitly acknowledges that we are able to improve. The problem with the negativity is that it is built on the notion that ... the best way to explain it is to revert, once again, to what we easily understand, non-African racism towards Black Africans. The racist theory that Black people are inferior presupposes that we cannot possibly be as good as anyone else, that we are automatically and irredeemably .... fill in the blank with negatives.

When certain Nigerians tout the division of the country as the "only solution" to our problems, or when people say that the Amalgamation was the source of all of our problems, there is an inherent belief that it is not possible to live in the same country with the other Nigerians, that it is not possible for us to live with them in the same country. Because they are just inherently and irredeemably ... fill in the blank with negatives.

I have had conversations with people where they start out agreeing with me in terms of critiquing the problems, but somewhere along the line, while I am still trying to analyze how we can all come together to solve the problem, the other person(s) branch off toward blaming another ethnic nation, geographical region, "geopolitical zone", or even senatorial zone for the problems. Even within a single town or city, the finger gets pointed at a socioculturally distinct neighbour (Ife and Modakeke, Aguleri and Umuleri, K-dere and B-dere, Zangon and Kataf), who is somehow to blame for the lack of jobs, the scarcity of land, and any other problems.

I know from experience that if you push through and continue arguing your case, those person(s) you are discussing with swing back from the knee-jerk response of blaming some other sociocultural group, and rejoin your analysis of what we could do together to fix the problem. However, the end of the conversation invariably involves both you and them concluding that it is unlikely that the problem will be solved in the real world.

As I've asserted in prior posts, this sort of negative political reaction to each other is the product of a sea of information in which we all swim.

Negativity, Violence and Shock Value sell newspapers and keep eyes attached to television sets. But while this is true of the commercial media everywhere, the overall nature of the discourse in most of the world's successful countries is to magnify and trumpet the best part of their national soul, and to sweep the less honourable parts of their national history under the carpet. Even what purports, in this age of political correctness, to be a less patriotic and hagiographic version of their history still rather underplays much of less edifying parts of their past; and much of what is presented as the "progress" of the present could be interpreted rather differently if one took a less rose-tinted view of events.

We do the opposite. We bury the best parts of our Federal Republic's shared soul, and overplay the worst parts of us. We not only treat the violent fringe as if it were the "normal" Nigeria, but go out of our way from an institutional and governmental point of view to facilitate the actions of the violent fringe as though we are not supposed to be otherwise, or rather cannot be otherwise. That is it right there. The idea that this, the violence, is who we are, and that it is not possible not to be this way.

But I didn't have to hear Father Kukah's story to know that the truth of Nigeria is quite different. In fact, while incidents of mass violence are rightly given wide coverage in the news, at any given point in time, most of Nigeria and Nigerians are not in fact subject to any violence.

Father Kukah's statement about violence and reprisal violence in the City of Kaduna, reminded me of a television report about two men who had previously been leaders of rival gangs of "youths" in Kaduna, gangs that attacked neighbourhoods of people from the sociocultural group of the rival gang (similar to what has been happening in the City of Jos since 1999). It was one of the few reports I had seen that didn't portray the violence as being one-sided.

These gangs are made up of youths who are unemployed, poor and prone to inducement by political factions. Indeed, a lot of violence in Nigeria is carried out by starving boys and youths who loot the homes and businesses of wealthier "foreigners" (i.e. non-indigenes). One of the more unfortunate aspects of our shared human history repeats itself: when poverty and economic uncertainty rise in any country (even in those so sure of their supposed "enlightenment"), the tendency is for gangs of poor, unemployed youths to see wealthy "foreigners" as having taken opportunities that should have gone to locals.

Of course, if we looked at it this way, we would have been obliged to fix the economic problems of our cities. But now that we just conclude it is ethnic or religious violence, we can throw up our hands and say there is nothing we can do about it.

What really struck me about the story is the two former gang leaders working together to end the violence in the city is how little coverage they received in the Nigerian media. They should be household names, but I only learned of them briefly and only from a foreign media source, not the Nigerian media.

It is time we gave greater prominence to stories of the good people, at least enough so that our people know there is another side to the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Here are links to previous posts I have made about stories that we should tell louder:

THE STORIES WE IGNORE An excellent feature by Tadaferua Ujorha for Daily Trust.

FIGHTING FOR PEACE An excerpt from a Weekly Trust essay by Carmen McCain about an old man who died doing the right thing, but who has been forgotten while we glorify and give national honours to the men and women responsible for creating the situation that killed this good man.

WE STAND TOGETHER Three articles.

GOOD DEEDS IN CENTRAL NIGERIA Self-explanatory (I hope the embedded links are still live).

Perpetuating the Propaganda Ourselves

In these posts (here, here and here), I talked about how other peoples sometimes work to create a negative opinion or prejudice about us among their people.

But we very often do the same thing.

Most countries in the world are able to maintain a public image in the rest of the world that is built on whoever is perceived to be the "best" of their population. Until recently, there was a global image of the British "gentleman" and "lady", even though there were many people in Britain whose conduct was closer to that of a football hooligan. The Japanese are known for being good at technological products, for being good at exporting things, and for the "salary man" in the world of business, even though there are many Japanese who do the most scandalous of things (some of the stuff they show on Japanese television is ... legally and without much fuss ... is downright weird, and that is putting it extremely mildly). The United States also projects an image to the rest of the world that is not really congruent with reality.

It is true that all of these places are richer than Nigeria. What is not true is the very loudly unspoken idea that they are richer than us because their people are "superior" to us, better than us at an inherent level, or that their culture is "superior" to ours.

Many of us tend to perpetuate these sorts of ideas. When a Nigerian does something bad, we the Nigerians react as though the person and the person's actions were symptomatic of all Nigeria and all Nigerians. Conversely, when someone does good, it gets dismissed or is not talked about quite as much as the bad person/thing.

It is strange that we label ourselves with negative things, and then talk about foreign countries, even African countries, as though they are completely innocent of those negative things. In reality, if you pick any particular negative act, and assign a Naira or Dollar amount to the absolute magnitude of however much of that act is done by Nigerians, and then do similar analyses of the "perfect" foreign lands, you will find that they do far more of it than we do.

Let me give you and easy example. For a while, the word "Nigerian" and the phrase "potential drug pusher" were used interchangeably by the immigration authorities at airports all over the world. The United States even went so far as to "decertify" Nigeria at some point for supposedly failing to act to control the illegal narcotics trade. Today, you still see the casual equation of "Nigerian" with "drug dealer" in the South African media (and I still regret the $10.00 I spent watching the South African-produced District 9).

But even at the high point of Nigerians being involved in the illegal narcotics business, the total "Nigerian" involvement was microscopic when compared to the United States, the various Western European countries and Japan. There were more of their citizens involved in the business than ours, a higher proportion of their citizenry involved than ours, and the Dollar amount of their involvement made ours look like 50 kobo groundnut money by comparison.

Yet nobody treated their citizens in total as if they were all guilty of drug crime until proven innocent.

This type of negative stereotyping is bad when it comes from foreigners, but we do it to ourselves.

Treating an individual person's crime as though it was a crime committed by his or her entire ethnic group is a recurring theme in our recent political history. And assuming that bad Nigerians epitomize all Nigerians is a standard reaction to any bad news about a random Nigerian in Nigeria or anywhere in the world.

Indeed, there is this mysterious tendency to question everything about ourselves and our society any time we hear that one of our number was caught doing something bad abroad. At best, he or she is said to be giving all of us a bad name. In the meantime, people from abroad have done, are doing, and will do far worse things on the African continent and in the wider world without any fear of being prosecuted for it. And nobody gives their whole country a bad name because of it.

Take all the snide comments about the so-called "Nigerian Scam" (a.k.a 419) on the internet. If you add up all of the money scammed by every Nigerian scammer that has ever existed, it would add up to less than what a single American (Bernie Madoff) scammed off of the people duped into investing in his Ponzi Scheme. Should we call such schemes the "American Scam"? Or should that term be reserved for the various exotic financial instruments and derivatives that nearly wrecked the entire global economy?

Look, before anyone start shouting insults at me, I am not trying to get people to place negative labels on foreign countries. Just pointing out that we Nigerians should stop accepting the negative labels other people place on us and should stop creating/propagating negative labels of our own.

Believe it or not, the super-majority of Nigerians are kind, decent, good people. If this weren't the case, the Federal Republic would have collapsed into anarchy a long time ago. Most of the things that are supposed to enforce the political "order" are dysfunctional or nonexistent, likewise the things that are supposed to support the economy (for example our banks lend only to "safe" borrowers like the government, import-exporters and Big Business), yet there is an "order" to life in Nigeria that is built on we the people effectively governing and "policing" ourselves.

Life in Nigeria often involves interacting with the institutions of state only insofar as there are certain things you have to give them (e.g. an extorted sum of money at a police checkpoint). Beyond that, it is often as though we don't have a government (or a "formal" private sector), yet we still manage to get things done. We generate our own electricity, provide ourselves with water, construct our own "roads" and generally get things done in an economic system built substantially on trust because nobody has the time or resources to enforce contracts through the court system. It is all on trust, something that doesn't exist if you believe the negative stereotype.

Yes, there are scammers who take advantage of the situation, but if the scammers were in the majority, everything in Nigeria would have long since ground to a halt. Life is able to proceed in Nigeria because we Nigerians mostly do the "right" thing without compulsion or coercion, and where we fall short it is usually because of the reality that condition bends the crayfish. There are situations in which doing the "right" thing is either difficult, impossible or metaphorically masochistic -- for example, a certain element of nepotism, kinsman-ism, clique-ism and ethnicism comes into play in an economic and political system built on knowing someone enough to trust them, rather than relying on impartial and effective judicial enforcement of contracts.

But we are not fundamentally bad people.

And don't let them get away with convincing people otherwise.

I often say that "communal violence" in Nigeria is predictable and avoidable, but for various reasons the powers that be refuse to do what is necessary to avoid it. Under normal circumstances, we the people should have reacted with anger to their failure to do the necessary, but we have allowed the discourse to be dominated by those who work to convince us that the entire sociocultural group to which one side or the other in these incidents belong are "bad people" who attack the other side because of the sheer "badness" of their entire sociocultural group. This is how "they" behave, is the basic response, and since there is nothing you can do to change "their" behaviour, we just have to live with the fact that "they" will keep doing this.

Do you realize that Nigeria would be an entirely different type of country if it was true that every member of every ethnic group hated every member of one or all of the other ethnic groups?

What we have now, in terms of violence, is what happens when the violent few are allowed to plague the peaceful majority from every sociocultural background.

We are also dealing, separately, with the fact that the most desperate economic groups in the country don't have anything other than violence to defend what few economic rights they have. Most "communal violence" in Nigeria revolves around land disputes between communities, about ownership of land, about who is or is not an indigene (i.e. has or doesn't have right to a portion of the land), and about the competing land-linked interests of farmers and pastoralists.

We are good people. And it is time we start believing that about ourselves.

But we very often do the same thing.

Most countries in the world are able to maintain a public image in the rest of the world that is built on whoever is perceived to be the "best" of their population. Until recently, there was a global image of the British "gentleman" and "lady", even though there were many people in Britain whose conduct was closer to that of a football hooligan. The Japanese are known for being good at technological products, for being good at exporting things, and for the "salary man" in the world of business, even though there are many Japanese who do the most scandalous of things (some of the stuff they show on Japanese television is ... legally and without much fuss ... is downright weird, and that is putting it extremely mildly). The United States also projects an image to the rest of the world that is not really congruent with reality.

It is true that all of these places are richer than Nigeria. What is not true is the very loudly unspoken idea that they are richer than us because their people are "superior" to us, better than us at an inherent level, or that their culture is "superior" to ours.

Many of us tend to perpetuate these sorts of ideas. When a Nigerian does something bad, we the Nigerians react as though the person and the person's actions were symptomatic of all Nigeria and all Nigerians. Conversely, when someone does good, it gets dismissed or is not talked about quite as much as the bad person/thing.

It is strange that we label ourselves with negative things, and then talk about foreign countries, even African countries, as though they are completely innocent of those negative things. In reality, if you pick any particular negative act, and assign a Naira or Dollar amount to the absolute magnitude of however much of that act is done by Nigerians, and then do similar analyses of the "perfect" foreign lands, you will find that they do far more of it than we do.

Let me give you and easy example. For a while, the word "Nigerian" and the phrase "potential drug pusher" were used interchangeably by the immigration authorities at airports all over the world. The United States even went so far as to "decertify" Nigeria at some point for supposedly failing to act to control the illegal narcotics trade. Today, you still see the casual equation of "Nigerian" with "drug dealer" in the South African media (and I still regret the $10.00 I spent watching the South African-produced District 9).

But even at the high point of Nigerians being involved in the illegal narcotics business, the total "Nigerian" involvement was microscopic when compared to the United States, the various Western European countries and Japan. There were more of their citizens involved in the business than ours, a higher proportion of their citizenry involved than ours, and the Dollar amount of their involvement made ours look like 50 kobo groundnut money by comparison.

Yet nobody treated their citizens in total as if they were all guilty of drug crime until proven innocent.

This type of negative stereotyping is bad when it comes from foreigners, but we do it to ourselves.

Treating an individual person's crime as though it was a crime committed by his or her entire ethnic group is a recurring theme in our recent political history. And assuming that bad Nigerians epitomize all Nigerians is a standard reaction to any bad news about a random Nigerian in Nigeria or anywhere in the world.

Indeed, there is this mysterious tendency to question everything about ourselves and our society any time we hear that one of our number was caught doing something bad abroad. At best, he or she is said to be giving all of us a bad name. In the meantime, people from abroad have done, are doing, and will do far worse things on the African continent and in the wider world without any fear of being prosecuted for it. And nobody gives their whole country a bad name because of it.

Take all the snide comments about the so-called "Nigerian Scam" (a.k.a 419) on the internet. If you add up all of the money scammed by every Nigerian scammer that has ever existed, it would add up to less than what a single American (Bernie Madoff) scammed off of the people duped into investing in his Ponzi Scheme. Should we call such schemes the "American Scam"? Or should that term be reserved for the various exotic financial instruments and derivatives that nearly wrecked the entire global economy?

Look, before anyone start shouting insults at me, I am not trying to get people to place negative labels on foreign countries. Just pointing out that we Nigerians should stop accepting the negative labels other people place on us and should stop creating/propagating negative labels of our own.

Believe it or not, the super-majority of Nigerians are kind, decent, good people. If this weren't the case, the Federal Republic would have collapsed into anarchy a long time ago. Most of the things that are supposed to enforce the political "order" are dysfunctional or nonexistent, likewise the things that are supposed to support the economy (for example our banks lend only to "safe" borrowers like the government, import-exporters and Big Business), yet there is an "order" to life in Nigeria that is built on we the people effectively governing and "policing" ourselves.

Life in Nigeria often involves interacting with the institutions of state only insofar as there are certain things you have to give them (e.g. an extorted sum of money at a police checkpoint). Beyond that, it is often as though we don't have a government (or a "formal" private sector), yet we still manage to get things done. We generate our own electricity, provide ourselves with water, construct our own "roads" and generally get things done in an economic system built substantially on trust because nobody has the time or resources to enforce contracts through the court system. It is all on trust, something that doesn't exist if you believe the negative stereotype.

Yes, there are scammers who take advantage of the situation, but if the scammers were in the majority, everything in Nigeria would have long since ground to a halt. Life is able to proceed in Nigeria because we Nigerians mostly do the "right" thing without compulsion or coercion, and where we fall short it is usually because of the reality that condition bends the crayfish. There are situations in which doing the "right" thing is either difficult, impossible or metaphorically masochistic -- for example, a certain element of nepotism, kinsman-ism, clique-ism and ethnicism comes into play in an economic and political system built on knowing someone enough to trust them, rather than relying on impartial and effective judicial enforcement of contracts.

But we are not fundamentally bad people.

And don't let them get away with convincing people otherwise.

I often say that "communal violence" in Nigeria is predictable and avoidable, but for various reasons the powers that be refuse to do what is necessary to avoid it. Under normal circumstances, we the people should have reacted with anger to their failure to do the necessary, but we have allowed the discourse to be dominated by those who work to convince us that the entire sociocultural group to which one side or the other in these incidents belong are "bad people" who attack the other side because of the sheer "badness" of their entire sociocultural group. This is how "they" behave, is the basic response, and since there is nothing you can do to change "their" behaviour, we just have to live with the fact that "they" will keep doing this.

Do you realize that Nigeria would be an entirely different type of country if it was true that every member of every ethnic group hated every member of one or all of the other ethnic groups?

What we have now, in terms of violence, is what happens when the violent few are allowed to plague the peaceful majority from every sociocultural background.

We are also dealing, separately, with the fact that the most desperate economic groups in the country don't have anything other than violence to defend what few economic rights they have. Most "communal violence" in Nigeria revolves around land disputes between communities, about ownership of land, about who is or is not an indigene (i.e. has or doesn't have right to a portion of the land), and about the competing land-linked interests of farmers and pastoralists.

We are good people. And it is time we start believing that about ourselves.

On the Inherent Risks of Political Protests

A Camerounian posted something on a popular Nigerian discussion forum. He was commenting on recent events in Egypt. For the record, I have not expressed an opinion on Egypt on this blog, and I am not going to do so on this blog. I will address something else about the Camerounian's comments.

Here is what he said:

Here is what he said:

Many people go out every year protesting for political reasons.Many die in the cause.In Egypt hundreds of people have died because they wanted one person, who might turn his back on them, to be placed back to power. I have been in protests before and I remember the dangers and group effect that make you do things you won't do if alone.I have come to see the world today different from the average person at least politically.

Some people really die protesting for what will not even help them or will not change their status.

Is it better to just ask for your bread and tea from the ruling elite and a house above your head and live peaceful till death takes us naturally? I love this life and won't go and die because i want to make it better for others because it doesn't get better at all and many people don't even get what they asked when they succeed in their protest.Nowadays I actually feel sorry for people going out and dying in protests. I will say do protest but if i sense it is getting out of hand, go back home. Dying is not worth it, what is your take?

It is a much more complicated issue than that, though, isn't it?

On the one hand, George Orwell's "Animal Farm" is a fairly accurate description of what happens following "coups", "revolutions" and other changes of government. One way or another, what comes after tends to bear a striking resemblance to what came before. All of the things that were supposedly fought against continue on, albeit under new management. And the ideologues and intellectuals that purportedly to argue in favour of changing things metamorphose into defenders of everything they previously criticized, insofar as their political faction is advantaged.

Indeed, one could argue that one of the many problems with post-colonial African countries is the "heroes of liberation" inherited all of the (undemocratic, unaccountable, unchecked) powers of the imperialists, as well as all of the coercive institutions created to impose that power on the citizenry (as well as political techniques like ethnic divide-and-rule), and have since proceeded to use that power in exactly the same manner without reform. The fact that our governments continue to take instruction from colonial-type world powers, whether directly (bilaterally) or indirectly (via institutions like the Bretton Woods agencies), only adds to the feeling that we have Black African Governor-Generals masquerading as Presidents.

On the other hand, I will admit to being tempted to tell the Camerounians that his attitude is the reason Paul Biya has been President of Cameroun for 31 years (and why Ahmadou Ahidjo was President for 22 years before Biya chased him out of the country. If he opens his mouth and says the wrong thing, Yaounde has only to threaten violent reprisal, and he will quieten down.

So, what is the answer?

I don't know. I don't think there are easy answers. I am not going to pretend to be an action hero myself.

As I said in the first paragraph, this blog post is not about Egypt.

Speaking about Nigeria, I do think that we the citizens are collectively to blame. We allow ourselves to be divided against each other so easily that we don't seem to realize that we collectively outnumber the totality of the squabbling political/economic factions that govern us. We not only outnumber them in the society at large, but we outnumber them in the Army and the Police as well.

Our overwhelming advantage was not brought to bear during the colonial period, and has not been brought to bear in the post-colonial period either. Even the soldiers and polices, who are drawn from us, from our families, have been shooting at us on behalf of governments, colonial and post-colonial alike, for more than 150 years (dating back to before the foundation of the Lagos Colony).

I am not sure any of us Nigerians would have to die to change Nigeria. We just have to collectively want it and collectively make it happen.

On the one hand, George Orwell's "Animal Farm" is a fairly accurate description of what happens following "coups", "revolutions" and other changes of government. One way or another, what comes after tends to bear a striking resemblance to what came before. All of the things that were supposedly fought against continue on, albeit under new management. And the ideologues and intellectuals that purportedly to argue in favour of changing things metamorphose into defenders of everything they previously criticized, insofar as their political faction is advantaged.

Indeed, one could argue that one of the many problems with post-colonial African countries is the "heroes of liberation" inherited all of the (undemocratic, unaccountable, unchecked) powers of the imperialists, as well as all of the coercive institutions created to impose that power on the citizenry (as well as political techniques like ethnic divide-and-rule), and have since proceeded to use that power in exactly the same manner without reform. The fact that our governments continue to take instruction from colonial-type world powers, whether directly (bilaterally) or indirectly (via institutions like the Bretton Woods agencies), only adds to the feeling that we have Black African Governor-Generals masquerading as Presidents.

On the other hand, I will admit to being tempted to tell the Camerounians that his attitude is the reason Paul Biya has been President of Cameroun for 31 years (and why Ahmadou Ahidjo was President for 22 years before Biya chased him out of the country. If he opens his mouth and says the wrong thing, Yaounde has only to threaten violent reprisal, and he will quieten down.

So, what is the answer?

I don't know. I don't think there are easy answers. I am not going to pretend to be an action hero myself.

As I said in the first paragraph, this blog post is not about Egypt.

Speaking about Nigeria, I do think that we the citizens are collectively to blame. We allow ourselves to be divided against each other so easily that we don't seem to realize that we collectively outnumber the totality of the squabbling political/economic factions that govern us. We not only outnumber them in the society at large, but we outnumber them in the Army and the Police as well.

Our overwhelming advantage was not brought to bear during the colonial period, and has not been brought to bear in the post-colonial period either. Even the soldiers and polices, who are drawn from us, from our families, have been shooting at us on behalf of governments, colonial and post-colonial alike, for more than 150 years (dating back to before the foundation of the Lagos Colony).

I am not sure any of us Nigerians would have to die to change Nigeria. We just have to collectively want it and collectively make it happen.

Ngugi: English is Not an African language

My comments:

(a) I am not sure why the interviewer kept claiming an author's books would not reach wider audiences if he or she wrote them in an African language. Books written originally in the English language are translated into other languages so non-English speakers can access them. A book written originally in Kikuyu or Ashanti could just as easily be translated for wider audiences. It is not that big of a deal.

(b) What really gets on my nerves is how African governments align themselves in "Francophone" and "Anglophone" blocs in continental and global diplomatic disputes and discourse. I cannot tell you in words typed on a blog how much that aggravates me. A man named Kouame Ousmane Cisse and another man named Kwame Usman Sesay will determinedly back "Francophone" and "Anglophone" candidates respectively, for no sensible reason other than a European language. Laughably, neither of the candidates, if appointed, would do anything that substantively improves the lot of the people of the sociocultural group to which both Kouame and Kwame belong.

The worst part of the "Anglophone"/"Francophone" discourse is the fact that these governments have yet to collectively articulate an African discourse on vital issues. Not an African position on the issues (which does not exist, in spite of talk to the contrary), but an African discourse. There are a billion people on the African continent; we are not all supposed to share the same position on issues, however we can come to better conclusions about those issues if we actually substantively discuss them as Africans.

Much of what is put out there as being in Africa's "interest", are stuff that are not in our interests at all. Much of what is put out there as being in Africa's "interest" are ideas and policy-decisions that were not generated by we Africans to begin with. And much of what our "intellectuals" come up with is very ideological (e.g. "Africa Must Unite") .... and the problem here is not just that there are very few practicalities in it, but that no one ever questions whether the ideology, if made practical, would advance or actually hinder the continent's progress.

But I am beginning to digress. If you haven't watched it already, here is the video:

(a) I am not sure why the interviewer kept claiming an author's books would not reach wider audiences if he or she wrote them in an African language. Books written originally in the English language are translated into other languages so non-English speakers can access them. A book written originally in Kikuyu or Ashanti could just as easily be translated for wider audiences. It is not that big of a deal.

(b) What really gets on my nerves is how African governments align themselves in "Francophone" and "Anglophone" blocs in continental and global diplomatic disputes and discourse. I cannot tell you in words typed on a blog how much that aggravates me. A man named Kouame Ousmane Cisse and another man named Kwame Usman Sesay will determinedly back "Francophone" and "Anglophone" candidates respectively, for no sensible reason other than a European language. Laughably, neither of the candidates, if appointed, would do anything that substantively improves the lot of the people of the sociocultural group to which both Kouame and Kwame belong.

The worst part of the "Anglophone"/"Francophone" discourse is the fact that these governments have yet to collectively articulate an African discourse on vital issues. Not an African position on the issues (which does not exist, in spite of talk to the contrary), but an African discourse. There are a billion people on the African continent; we are not all supposed to share the same position on issues, however we can come to better conclusions about those issues if we actually substantively discuss them as Africans.

Much of what is put out there as being in Africa's "interest", are stuff that are not in our interests at all. Much of what is put out there as being in Africa's "interest" are ideas and policy-decisions that were not generated by we Africans to begin with. And much of what our "intellectuals" come up with is very ideological (e.g. "Africa Must Unite") .... and the problem here is not just that there are very few practicalities in it, but that no one ever questions whether the ideology, if made practical, would advance or actually hinder the continent's progress.

But I am beginning to digress. If you haven't watched it already, here is the video:

For the Record: On the State of Emergency in the Northeast

I haven't said anything about it. And I am not going to now.

I often say on this blog that it is difficult to know what it actually happening, anywhere in the world. You can't trust politicians, and you can't really trust the news media, be it "mainstream" or "alternative" (especially on issues of real importance). There are a lot of people in the world who talk as though they are "experts" on what is going on, and other people who differ from and criticize the "experts" based on their belief that they are more correctly informed about what is going on than the "experts". Strangely, an ever-growing proportion of younger people get their "news" from comedians who are not necessarily funny or particularly insightful. The comedian-as-expert concept reached a new high at the last Italian elections, when a political party founded by a comedian did exceptionally well.

At the end of the day, even if you read/watched/listened/studied everything said by everyone from every conceivable bias and pretension to "expertise", if you were fully honest with yourself, you would admit that you don't actually know what exactly happened, who exactly did what, how exactly they did it, and why they did it ... even if the results of whatever happened directly affect you.

You may ask whether I am being a hypocrite, since I write a blog and offer opinions on the issues.

Perhaps. But what can you do?

I will say this: My intent with this blog is not necessarily to comment on specific items of "news", but to talk about the issues generally. In other words, my response to a news article about a specific thing the Inspector-General of Police reportedly/allegedly did would be to engage in a broader discussion of why the Nigerian Police Force functions the way it does, why there has not been (and will not be in the near- or mid-term future) any reform of the Nigerian Police Force, and why nothing substantive about the operations of the Police will change until such and such reform is instituted.

Such commentary, be it sensible or silly in your opinion, is not necessarily tied to whether or not the report on the Inspector-General of Police is factual, counter-factual, partly-factual, or polemical.

The problem with commenting on the State of Emergency in the Northeast is .... people are dying. Soldiers are dying. Civilians are dying. Suspects are dying. Criminals are dying.

I am not comfortable forming opinions, much less commenting, on this type of thing when I do not actually know what is going on.

Eventually, things will calm down, the dust will settle, and we will all be able in theory to get a better handle on what happened (past-tense). Emphasis on "in theory", because to be quite honest, we the people of Nigeria have little or no certainty of information on what happened in the three ECOMOG wars, the Somalia mission in the early 1990s, the various coups, or the Civil War. What information as is out there is quantitatively insufficient, and qualitatively dubious.

It doesn't help that our fractured politics distorts analyses to begin with.

Speaking of politics, one of these days, someone will do a credible, mathematical analysis that will show that the Fourth Republic has been the most corrupt period of our history, and the second-most violent (behind only the 2.5 years of the Civil War). By and large, the politicians are responsible for the various violent crises that have hit the Federal Republic, one-after-another, since 1999, sometimes by deliberate commission and other times by equally-deliberate omission.

So you will not see any commentary from me on the State of Emergency.

What I can say is I wish nothing but the best for the people of Borno, Yobe and Adamawa.