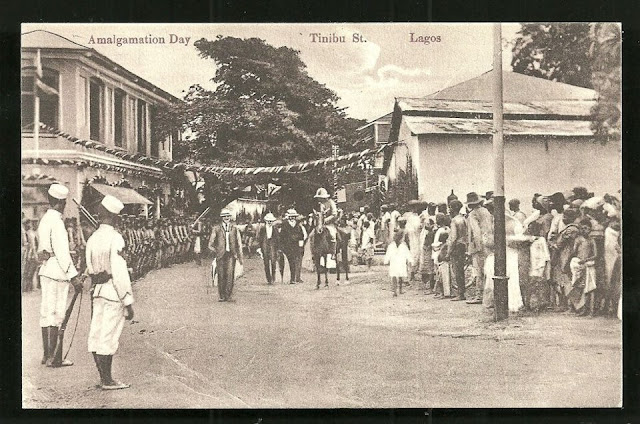

Amalgamation Day in Lagos, 1914

26 February, 2009

21 February, 2009

Goals for the 2010 World Cup

I love the Eagles. We have been fairly successful in African competition in the 39 years of the modern football era (i.e. since 1970). Still I would say we have underperformed somewhat. We have not lacked for opportunity, but have been persistently weak at converting opportunities.

In three decades of Nations Cups from 1978 to 2008, Egypt won five titles from five finals (a 100% conversion rate), Cameroun four from five finals (80% rate), and Ghana two from three (66%). In the same period, Nigeria reached the final six times, the most of any team, but won only twice (33%).

Our true conversion rate is actually worse. Due to the 1996 boycott and 1998 suspension, the Eagles participated in 14 of 16 Nations Cup tourneys between 1978 and 2008, and finished in the top three 11 times. Effectively we won just 2 continental titles from 11 golden opportunities – an 18% rate.

It reads like a metaphor about our federal republic – gifted with golden opportunities lost or wasted.

The Eagles are a perennial big fish in the continental lake, but have made no sustained impact on the ocean that is global football. I do not mind being a top dog in Africa; I wish Nigeria had the most African titles, not Egypt, and that we had beaten Cameroun in those three finals. But the lack of global success makes the African success seem hollow.

Our women’s national team, the Falcons, crystallized my thoughts in this regard. The Falcons absolutely dominated Africa for two decades, with nothing to show for it at the Women’s World Cup or Olympics other than a single Cinderella run to the final eight in 1999. If the continent’s female juggernaut is a relative weakling in global competitions, you have to conclude the quality of Africa’s women’s teams is poor in global terms – which gives me the same feeling about our continental success as I get when I read about teams winning the East African CECAFA Senior Challenge (a competition made up of teams that never qualify for the Nations Cup – no offence).

And is it really different on the men’s side? I mean, we hype the quality of our superstars, and make fun of “boastful” teams like England (never mind that we have never equalled their World cup record), but in cold hard reality, what have we done to back up the boasts?

It pains me as a Nigerian to admit it, but if you add up the statistics for both the Nations Cup and World Cup, the Lions of Cameroun were the most successful African team of the last 31 years (i.e. from 1978); and other than a single Cinderella run to the quarterfinals in 1990, the Lions did little at the World Cup. Before anyone blames the African qualification process, the Lions qualified five times in those 31 years, plenty of time and opportunity to show steady upward progress, but were knocked out at the preliminary stage four times (same as that other perennial qualifier, Tunisia).

Egypt, Nigeria and Ghana, who are arguably the second, third and fourth best African teams since 1978 could complain about not qualifying enough. But I don’t think the qualification format was Nigeria’s problem. Remember what I said about our problem with converting opportunities? We only barely lost out on World Cup places in 1978, 1990 (to Cameroun) and 2006. My memories of 1978 are fuzzy, but off-the-field issues between players, administrators and managers decided our fates in 1990 and 2006. With that said, Nigeria is the only African team to make it out of the preliminary round of the World Cup more than once, the closest thing Africa has got to a team who can argue that their good performance was not a one-off fluke. But is a Second Round exit really a “good” performance? Should we act and think as if “Second Round” is the best we can achieve? Oh, I am sorry, what am I saying, we didn’t even qualify in 2006, and I am raising my hopes for getting past the Second Round.

I am focusing only on full senior international football. Our record in age-restricted events does not count. Why get excited after victory over a bunch of boys, if we will not be able to beat them when they are men? We beat Brazil in the 1996 Olympics semi-final, but it was Brazil who went on to the 1998 World Cup final and the 2002 World Cup title. The Brazilians thought it a failure to be knocked out of the 2006 World Cup at the quarterfinal stage – Nigeria can only dream of such “failure”. And after winning that Under-23 title (using senior team players who had already won a Nations Cup and played a World Cup) we decided an all-attack, no-defence team could “score 16 if they score 15” at the 1998 World Cup (with apologies to Dan Amokachi). It did not happen, did it? Yes, we continued to do “well” in Africa, but where is the world-level payoff? After watching our senior team huff and puff to a bland exit against grown men at Ghana’08, I was not consoled by watching our Beijing’08 team utterly dominate young boys. It was exciting 24 years ago when we won the Under-17 World Championship, but I would trade the Under-17 trophies we won in 2007 for a third Nations Cup crown or a single appearance at a World Cup semi-final. Heck, I’d trade our 1996 Olympic gold medal for a 1998 World Cup semi-final place!

Youth competition is useful only insofar as it gives tournament experience to players who could step up to the senior team. The 2005 Under-21 World Championship gave us John “Mikel” Obi and Taiye Taiwo. The highlight of Beijing’08 for me was the intelligent performance of Solomon Okoronkwo; not since Finidi have I seen such a natural at right-midfield in an Eagles jersey. And while the jury is still out on the 2007 Under-17 African and World Champs, Rabiu Ibrahim could make the step up, with a bit more maturity – but only if we stop the “new JJ” talk, and ponder instead how he will differ from left-midfield predecessors Emmanuel Amunike and Garba Lawal.

At the senior level, Nigeria’s Eagles have been in decline since 1994, and even then we were not as strong as our hagiographic memories make us out to have been. In fact, we would have been better off if in 1994-1996 we had spent more time thinking about our weak points, and less time celebrating our self-anointed status as Africa’s first world football power. We have continued to decline, fifteen years now, all the while still so insistent that we are the best. Hey, we win kiddie trophies and African Women’s Cups, right? The Nigerian Football Federation wasted a million dollar corporate sponsorship paying German managers, because they (like we) believed that the team was really okay, that the only problem was Nigerian managers didn’t know how to bring out the alleged strength of the team. At the end of the day, not only was Ghana’08 our worst Nations Cup, but we lost to Cote d’Ivoire in 2008 by the same score-line as the 2006 loss that cost Austin Eguavoen his job.

Why am I sounding this harsh? Simple: We will never work as hard as we have to transform our fortunes if we never admit just how far behind our long-term goal we actually are. We continue to act as if all we need is a little tweak, as if beating Sierra Leone means our problems have gone away.

The Eagles are a more important symbol of Nigeria than the flag or the anthem. We must arrest the decline, make a U-turn, and begin climbing back up towards the top. And not just the top of Africa; we must strive to join the GLOBAL football elite.

But here it is not going to happen overnight. It has been 15 years of continuous decline, and we are not going to zip into the World Cup semi-finals barely two years after a forgettable Ghana’08.

We must set simple targets, with simple timelines, and simple methods of measuring our progress towards those goals. Instead of a series of presidents promising to fix the entire electricity mess, why not a simple promise at the beginning of the year to add X-thousand mega-watts to the grid by the end of the year? We citizens can then monitor the construction or rehabilitation of a power station over the following year to see if anything is actually being done to fulfil the target. If it works, set another simple target for the following year, and if it fails, figure out why it failed by the beginning of the following year.

The same applies in football.

As far as the World Cup is concerned, our goal is to QUALIFY. After the disaster of 2006, we need to put aside our hubris and pomposity, and just work on qualifying.

If we qualify, and only if we qualify, we can then move to the next goal – creating a team that will be competitive in our guaranteed three matches at the World Cup. Any expectation other than that, and we set ourselves up to fail in the long-term, because we will end up sacking the team’s manager and perhaps disbanding the team for not living up to our unrealistic hopes.

The Eagles have had 10 managers in the last 11 years. Our current manager, Amodu Shuaibu, had three stints in that time, so we have really had 12 managerial episodes in 11 years. We have also “experimented” with and capped a prodigiously large number of players. And all of that added up to the bland display at Ghana’08.

Why don’t we do something different? We can make a plan, something we talk a lot about but rarely do, and give a single manager a five year run with the Eagles, from 2009 to 2014. He has to be someone known for building teams (not collections of individuals), and has to be someone we trust enough that we can stick with him even when we hit the inevitable tough patches. Mind you, we did have some stability between 2002 and 2005, so it should not just be stability for its own sake, but a deliberate plan to build a team for the 2014 World Cup.

Yes, I said 2014.

We should try to do well in 2010 (if we qualify) and should try to make the semi-finals (if it is at all possible, even via Cinderella Run) but we shouldn’t lose hope in ourselves if it doesn’t happen in 2010. And we should tell any manager that if the Eagles make it into the 2010 World Cup, he has to take an age-balanced squad comprised of veterans who will not make 2014, players in their prime who will be the veterans in 2014, and youngsters who will be in their prime in 2014.

Above all, we should NOT saddle them (players and manager) with unrealistic expectations. Not only could we end up making knee-jerk decisions, based on short-term disappointments, but the pressure could even be counter-productive in terms of the players’ performance on the field.

Dial down the pressure.

The target right now is qualification.

20 February, 2009

Diasporans get the vote, Angolans don't

Maurice Iwu, head of INEC, the Independent (yeah, right) National Electoral Commission,

hinted on the possibility of extending voting rights to Nigerians living abroad in the next general electionas the Guardian put it.

Professor Iwu made his remarks while receiving Edeltrudes Costa, Angola's Vice Minister for Territorial Administration and Electoral Matters.

The Angolan minister said he was in Nigeria to meet with Prof Iwu:

to understudy how Nigeria conducted the 2007 elections ... noting that Angola was also desirous of having such a successful transition.

Yeah ... I am sure Angola wants EXACTLY the sort of "successful transition" we had in 2007. Na wa.

19 February, 2009

On the Joint Constitutional Review Committee 1

There should be 25% fewer total federal legislators in a single parliamentary chamber, rather than two.

The “Federal Capital Territory” should extend no further than the limits of the current Abuja Municipal Area Council; the rest of the current FCT should be transferred to the most appropriate of the 7 proposed states. The new, reduced, FCT would be one of four geographically dispersed cities we should designate ‘federal territories’ and keep unaffiliated to any of the 7 states.

Redesigning internal boundaries is much less contentious than determining the rights and privileges of “indigenes” and “non-indigenes” in any given area. Then there is the even more dangerous question (in certain parts of the country) of exactly who qualifies as an “indigene”. It is a delicate thing, this debate over constitutional reform and broader restructuring.

The dominant theme in Nigerian politics since the 1950s has been the pervasive, reciprocal fear that other socio-cultural groups would become powerful enough to “dominate” or “marginalize” your own group. Fear makes substantive reform next to impossible, as citizens are more afraid of fellow citizens than they are of a non-performing government or under-performing economy. It is consequently easy for a few to exercise unchecked politico-economic power over many. The defensive walls we citizens raise against each other are the unshakeable platforms on which politicians, militicians and plutocrats securely stand to make the invisible deals that rob the rest of us of our right to choose our governments (directly) and their policies (indirectly). The British colonialists exploited our inability to create a unified response.

Mutual fear is both cause and symptom, as we Nigerians have also struggled to correctly identify what constitute our REAL interests as citizens, communities, ethno-cultural groups and as a federal republic. We ignore the crucial, while investing energy and resources in self-defeating initiatives. I am no fan of external interventions, but the energy we spent fighting each other in the one major and many minor wars of the 1960s could have been better used fighting Apartheid or forming the first blocks of a sub-regional bulwark against the rise of “Mobutus” in West and Central Africa, and against the manipulations of great powers prosecuting their Cold War on African soil. We lost what could have been a huge trading partner (i.e. a potentially very wealthy Congo-Kinshasa) and gained a million lives lost to fratricidal conflict.

It is bad enough that we were excluded from the process of constitution-drafting, worse that even if we were included, we quite probably would have endorsed the decisions they made anyway, mistaking their interests for ours. So we did not have the democratic power to check our leaders, and may not have used the power effectively had it been given us.

This is important, because in the absence of institutional checks on instinctive behaviour, human beings will seek to maximize their own individual, rational self-interests. It has been a longstanding issue in the land of the Niger-Benue Confluence, predating colonialism, but I will restrict this post to “constitutional” issues since the Amalgamation.

Statistical micro-minorities with interests distinct from the broader population have controlled Nigeria’s constitution-drafting and approval processes in Nigeria since 1914, free to act on their impulses as there were no substantive democratic checks on their decision-making.

Our first constitutions were drafted by British colonial governors and approved by British parliaments. These averred that we the people had no right to control our governance, and no right to a mechanism for holding our government accountable for decisions and actions that affected us profoundly. The nascent colonial army and police were made responsible for defending a sequence of illegitimate regimes against any revolt by the people and for enforcing those regimes’ will on the people. Sound familiar?

The constitutional conferences in the 1950s, ahead of Independence, revolved around indisputably great men who nevertheless deeply distrusted each other, doubted the “Nigerian project”, and had no vision or conception of what “Nigeria” was or what “Nigeria” meant beyond the fact that it existed and shouldn’t be ruled by the British. They ultimately drafted a constitution that did much to protect their respective exclusive spheres of power from extra-regional and intra-regional rivals, but did little or nothing to create a new social contract to bind ALL of the diverse peoples of “Nigeria” to a common purpose.

The constituent assemblies and constitutional conferences of the 1970s were influenced by the aftermath of war, and the desire to avoid another one. There were controversies (and a coup) linked to the suspicion of tenure-elongation. Significantly, the 70s also saw the rise of a new class of elite politicians, militicians and plutocrats. These emergent New Big Men slowly and ponderously moved away from the rigid ethno-cultural camps of the 1950s and 1960s, toward a sort of pan-Nigerian grand alliance of Big Men. It took three decades, and quite a bit of (at times violent) intra-Big-Man strife, before the alliance was perfected as the “Peoples Democratic Party” in 1999. The Big Men’s struggle between and within themselves to define their relationships to each other was more influential on the constitutional and structural nature of Nigeria during this period than anything we the people needed or wanted.

Since 1999, there have been three attempts to “review” and/or “amend” our latest constitution. The first two tries took place during the Olusegun Obasanjo administration, and are notable only for the demise of the “Third Term” agenda. The only thing politically consistent about Nigerian Big Men is they inevitably move to bring down (dead or alive) any of their number they perceive to be garnering “too much” power relative to the rest of them; any other circumstance they are content to back “Any Government In Power”.

Nigeria in 2009 is constitutionally and structurally “perfect” for the PDP and the PDP-esque opposition, but quite imperfect for the rest of us. The PDP, which prides itself as Africa’s largest … gathering of Big Men, has controlled the Federal Republic for a decade. Oddly, the PDP in 2009 is assuring us they will review and amend the 1999 constitution. They have setup an 88-member Joint Constitution Review Committee (JCRC), comprised principally of Senators and Representatives. Per Nigerian constitutional tradition, they have promised to consult “stakeholders”. And I do believe (though I can’t find a reference) they have promised their new constitution will be put to a referendum.

They have not explained why we should believe the referendum will be any more democratic than the 2007, 2003, and 1999 elections. In fact the 2007 elections were so discredited, the Senators and Reps do not really have any mandate from Nigerians do deliberate on an issue as sensitive as a constitution, or on any issue at all. Even if we discount the rigging on the day, and the half-sensible, half-dubious tribunal and court decisions that followed, none of the major candidates or political parties in 2007 campaigned on any specific, substantive issue of national restructuring or constitutional reform, so none of the elected officials can claim the voters endorsed the ideas they intend to inject into the JCRC process.

Also unexplained is why we should believe the system can correct itself. A 7-state federation abolishes 29 gubernatorial posts. Sitting governors would lose their second-term birthright, and aspirants would have fewer positions to seek in the future, and would face a lot more competition for those spots, the two things they were trying to avoid when they fought for the creation of smaller states. Virtually all of the vital reforms and restructuring would disadvantage those Nigerians with the greatest ability to influence social, political and economic outcomes in the country. In the absence of a mechanism for citizens to over-ride these interests, why are we supposed to believe this constitution-drafting process will be any different from the other thousand or so we’ve had since 1914? Don’t say “referendum” until you have explained why we should believe it will be any more credible than any of the other elections we’ve had.

This brings us to the most powerful truth of all: It does not matter what constitution we have now, or what constitution we get in the future because at a fundamental level, the Big Men do not give a damn what the constitution says or doesn’t say. Our military-led diarchies needn’t have bothered suspending the constitutions after their coups, as the civilians never complied with the substance and spirit of those documents to begin with. Hilariously, the colonial constitutions gave the British the power to do whatever they wanted regardless of what we the people wanted, which was (in its way) more honest than our latter constitutions. What is a constitution anyway, and what value does it have, if it never reflects our reality in any way that can make an actual difference in our lives?

This is the conundrum, the challenge of our time as Nigerian citizens, the responsibility we have to the generations that follow us.

How can we the people break free of these constraints? How can we debate a proper social contract that can bring us together in the pursuit of our common interests and common goals? And how can we make that document “stick”, make it matter, give it substance and effect, not just in form but in spirit?

I’ll get to that … in the weeks or months ahead.

Stick with me.

PS: Anyone who takes the JCRC seriously should read this summary of their first steps on the road to constitution review. The 88 members have yet to say anything to give us an insight into the constitutional ideas each of them will bring to the table, so we citizens can debate the same. No, the first priority is to jostle for position (and related control of the committee budget).

10 February, 2009

The Minister of Defence of Madagascar resigned

28 citizens of Madagascar were killed by soldiers during anti-government protests on the weekend of February 7-8.

In an ideal world, the people of Madagascar would get rid of the autocratic Marc Ravalomanana and the opportunistic gambler Andry Rajoelina, and elect Cecile Manorohanta as their new president. She might be the first politician in Africa to take so clear and decisive a stand against using the power of government (in this case the killing power of security forces) to crush the opposition.

All over the continent, Ministers, even those with (supposedly) "progressive", "intellectual", and "technocratic" credentials keep quiet when their boss veers off in a destructive direction. None of them wants to lose their cushy job, perks, and benefits.

Closer to home, I wish Nigerian politicians, militicians, plutocrats, godfathers and sundry Big Men and Women took responsibility for outcomes of their decisions and actions (or inactions) rather than constantly insult our intelligence with hollow excuses. Mrs Manorohanta did not give the order to the troops, but they fell under her ministry so she stepped down.

A lot of people criticized ex-President Obasanjo when he scolded the grieving families of the victims of the Ikeja Cantonment munitions explosions, tell the them they should be grateful that he lowered himself to even come and look at them, but Obasanjo was just the visible face of the prevailing socio-political environment. The rest of the system of social, political and economic leadership may be more discreet and genteel about it, but their actions evince negligence and irresponsibility at best, subtle malevolence at worst.

To be honest, we the people do not hold them to account, do we? I mean, no matter how utterly useless a person in any leadership position happens to be, his kinsmen will defend him to the hilt. You see, he is not there to serve effectively, rather he is there to be a representative "mouth" from his part of the country on the table where "national cake" is served. If not the high table, then a side table, but damnit anyone who tries to remove him will taste the wrath of his kinsmen. It is not something peculiar to one part of the country; it is something we all do.

Even if you take out the "kinsman" phenomenon, you run into citizens praising men like Nuhu Ribadu, rather than holding them to account for what could only be described as failure. And please don't make excuses. If it was not possible for him to do what his supporters think he really wanted to do, he should have stepped down, resigned and run for office with all of his fans' support. Don't give me that "work within the system" talk, because that never works, as you his fans are now finding out.

Thank you Mrs Cecile Manorohanta. In a different universe, she would be a leading contender for Chairperson of the African Union Commission. In this universe, that job is held by Jean Ping, a man notable only for being an acolyte of life-President Omar Bongo of Gabon.

07 February, 2009

Welcome to the New Federal Republic

Welcome. Lafia. E kaabo. Nno.

Next year, on the 1st of October, 2010, the Federal Republic of Nigeria will mark fifty years since the end of British imperial rule. And an even bigger anniversary is on the horizon, less than five years away. On the 1st of January, 2014, it will be a hundred years since the 1914 Amalgamation created “NIGERIA”.

With two big anniversaries coming back-to-back (so to speak) the people of Nigeria should be taking stock, thinking about where we are, where we’ve been, and where we are going.

I love Nigeria. I love our many cultures and nationalities, our people and our geography. Diversity is a beautiful thing, even if we don’t realize it yet. Reject the popular pessimism, and the mythologized view of “the good old days”, a perfect past that never was. Do not deny that Nigeria has made progress, and is a better place today than it was in the colonial and pre-colonial periods.

But has our progress has been slower, shallower, narrower, less rooted, and smaller scale than could have been achieved with a different set of decisions and actions? If it has, what decisions and actions should we take going forward to accelerate our development?

Take the lasting national economic emergency that is the electric power generation.

My hometown did not have electricity in 1960. No one complained or was “angry” about it back then; our expectations of life were different in those days. After more than thirty years, and with a lot of self-help (e.g. buying a transformer with community contributions since the government and NEPA claimed to lack funds), the town was at last connected to the national grid. As you know, the grid does not have enough juice to power Lagos, much less all of Nigeria.

This is the Nigerian conundrum.

On the one hand, there is clear progress; one town is many steps closer to the goal of electricity than it was in the so-called “good old days”. Nevertheless, considering the critical role of power and energy in a modern economy, is this really the best we could have done after fifty years?

Let me try to illustrate how far we are from where we need to be. With a third of Nigeria’s population, and per capita income (reflecting economic activity) five times higher than ours, 45,000MW of supply is insufficient to free South Africa from sporadic blackouts. I offer a layman’s suggestion that 150,000MW will be insufficient for Nigeria to fully function at the height of its economic possibilities. It is a travesty that Nigeria produces only 4,000MW from a pathetically insufficient installed capacity of 10,000MW.

We are so far behind, it is not funny.

And fifty years is sufficient for rapid progress and development.

The world’s wealthiest countries completed industrial revolutions and socio-economic transformations in less than half a century. Nigeria has had the benefit of 20th and 21st century knowledge, where some countries worked with no more than 19th century information and technology. The late Deng Xiaopping opened up the Chinese economy 30 years ago, and rapid change began 20 years ago. Do not use China’s size as an excuse; read scholarly and non-scholarly works comparing African countries (e.g. Ghana) and Asian countries (e.g. Malaysia) that were on economic par fifty years ago. And please, don’t point to the countries that have done worse than us; such regressive thinking is why we officially pride ourselves on being the “Giant” of the world’s poorest and politico-economically weakest continent. And we are not even that: South Africa has a bigger economy, Cameroun more success in football, Botswana better governed, Benin Republic more democratic, and Egypt more geo-strategically relevant.

Ninety-five years ago, the British amalgamated us into a single political entity. They could do it because they had the power to do so and the will to exercise that power thus. The experience of subjugation should have taught us that being scientifically, technologically, militarily, economically, and politically weaker than other nations exposes us to their exercise of raw power. Rapid progress after 1960 should have been our target, not six years of political strife followed by 30 months of war.

Nigerians complain and criticize a lot, and I am glad we do. One reason we lagged in past historic epochs was our sense of contentment with what we had. In the “good old days”, we did not expect better, and did not demand better. Nowadays we want more, and we are frustrated that we are not getting it.

This is good. But are we demanding the right things?

Over the last fifty years, we have invested a lot of energy doing things that had little or no relevance to what we need to move our federal union forward.

In the latter half of the 1960s, Nigeria mobilized two armies that collectively fielded perhaps half-a-million soldiers (or more) over the course the Civil War. Combining these two armies and deploying them, suitably equipped and trained, against the Apartheid war machine in 1967 would have been the proportional equivalent of attacking Nigeria in 2009 with an army of 28 million soldiers. The Apartheid regime ostensibly represent 2.26 million South Africans of European descent in 1967 – and the near-20 million black South Africans in 1967 would proportionally translate to a 1.4 billion-person fifth column in 2009’s Nigeria. It was a numbers game they could not have won, given equal technology and training.

Another example. Think what good over 500 thousand soldiers could have done in the Congo-Kinshasa in the 1960s. The armies of Mobutu and Moise Tshombe together numbered far fewer. In this alternate universe, wealthier versions of Nigeria and DR-Congo could have been huge trading partners by now, driving trade and wealth creation across West and Central Africa. In either case, South Africa or Congo-Kinshasa, the casualties would likely have been fewer than the number of citizens Nigeria lost to major and minor violence between 1960 and 1970.

I am not advocating war. I hate war. But I want you to realize Nigeria has always had the resources to do the vital things we need to do to create a platform for true growth and development. Nothing has been out of our reach, its just we have not bothered to reach for them. For example, it is hard to be a force for citizen democracy in Congo-Kinshasa when we were quite incapable of it at home in Nigeria.

It could all have been different. Nothing was written in stone. If our outcomes have not been optimal, blame our choices, decisions and actions. In fact let us admit that the constant distinction we like to make between “military” rule and “civilian” rule is an excuse, an obfuscation designed to free we the people from responsibility. The “military” and “civilian” (who are often the same people, or share the same basic “ideology” if you can call it that) are both outgrowths of Nigerian society, reflecting our vices and exploiting our self-inflicted divisions. Today, some of us very conveniently heap the blame for our frustrations on current President Umaru Yar’Adua. Leave the man alone! He is not the one who created the system. We have changed presidents more frequently than most countries in Africa or Asia; when will we realize that we have to change the system if we want different outcomes?

We have to elevate the discourse. We are arguing about the wrong things. In fact, Nigerian politics has been a long, loud, loquacious, sometimes violent argument about NOTHING.

Think about it. In all of the malarkey before, during, and after the discredited 2007 general elections, do you recall any candidate saying anything that convinced you he had a plan to address the electricity crisis?

The current socio-political environment will not produce a solution to communal violence or electricity or anything else in the near or distant future. With the fiftieth anniversary of Independence is upon us, and the centennial of Amalgamation just behind it, let us slow down and take the time to think. Think deeply. Then we must decide. And after we decide, we must do, and do with all of our collective might.

Join me. Let’s ponder our past, consider our present, and argue (yes argue) about how to chart a stronger future.

I don’t mind if you disagree with me. In disagreeing you will probably make more sense than anything in our current political discourse. Indeed, as much as I am a supporter of Nigerian unity, I recognize that if Nigeria was a truly democratic place, there would be political parties (and concomitant voters) doing what the SNP is doing in Scotland, or what the Parti/Bloc Quebecois is doing in Canada. So I want to hear from you, from all of you.

You will certainly hear from me. I intend to talk about anything and everything related to the future of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, from the constitutional review process to the national football teams.

Did I mention there is a World Cup next year?

Welcome to my blog. I am new at this, and it will probably take me a couple of weeks to work out the kinks. Stay tuned, the debate is just beginning.

Oh, and I’ll try to keep my posts to two pages and under. It is hard to do when dealing with complicated issues, but I’ll give it my best shot.