As I always say, it is difficult to know what is actually going on in the world. Politicians, the media, academics and other so-called analysts, so-called "experts" in general, they all like to talk as though they know what is going on, but a lot of the time they don't, and even when they do they tend to tell the rest of us an edited (at best) or blatantly distorted (at worst) version of what is happening, with the intent of getting us to come to certain conclusions (i.e. the conclusions supportive of their agenda, whoever they happen to be).

There has been a lot of "low intensity" conflict in South Sudan since its separation from Sudan. Of course, no conflict is "low intensity" to the people who get killed, to the families left behind, or to the communities negatively impacted by whatever metric. The current political impasse may or may not lead to a bigger civil war (and one suspects outside players, regional and global, will bring pressure to bear on the key leaders to avoid open war), but it is likely that the state of low intensity conflict will continue.

In this, both Sudans are the same. The erstwhile "North" Sudan is also a place of constant, ceaseless, simmering conflict.

As a Nigerian, I am used to people who claim dividing a country will somehow solve the country or countries' problems. I have always wondered why people think that. It doesn't make any sense. If you divided Nigeria, each new piece will inherit every problem is already has ... and will also inherit the same useless political leaders that have already proven useless at solving the problems.

There is this tendency to point to the Czech and Slovakian republics as some sort of example. I am tempted to ponder whether the example is as great as is portrayed, but the fact of the matter is even if it were the most perfect example of separation ever recorded, it would still remain the case that both subsequent countries inherited status quo ante conditions from the preceding Czechoslovakia that are absent from other areas that are often portrayed as potential beneficiaries from the same outcomes.

Besides, the European continent is an odd place. Every few decades, there is a dramatic adjustment of internal borders that is hailed as a sign of great statesmanship, and is treated as though it were not only permanent but also a solution to all the problems that had existed before the realignment of borders. After some years, or some decades, there is another upheaval, whereupon borders change dramatically again. With all due respect, and meaning no offence to either country or to the citizens therein, but there is no particular reason to believe the Czech or Slovak republics will remain as they are indefinitely, or even that the future citizens of both countries will remember the separation fondly.

Heck, contrary to popular belief, the entity "Nigeria" as currently constituted might outlast the current European borders; as it stands, we have already outlasted the USSR, the GDR, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia. It seems Belgium is under stress, the Scottish National Party is flirting with a referendum, and one wonders if the much-ballyhooed European Union has more staying power than the Nigerian Federal Republic.

Look, I am not trying to offend anyone, but problems are problems. You either solve them or you don't. I am not overly fond of Felix Houphouet-Boigny's politics, but there is a statement credited to him (I don't know if he really said it) on the topic of uniting all former African colonies of France into one country. He asked whether they were all supposed to unite and share each other's poverty.

Uniting two poor countries won't make a rich one. Dividing a poor country will not create two rich ones. Dividing a violence-prone country creates two violence-prone countries. Dividing a lawless country creates two lawless countries. The Czech and Slovak republics did not become relatively wealthy because they were divided, and they would not have been relatively poor if they had stayed together.

That is all I am saying.

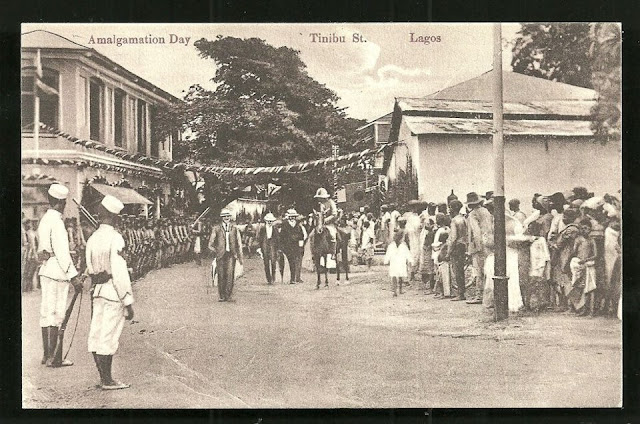

Amalgamation Day in Lagos, 1914

Showing posts with label African Politics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label African Politics. Show all posts

20 December, 2013

16 September, 2013

On the Inherent Risks of Political Protests

A Camerounian posted something on a popular Nigerian discussion forum. He was commenting on recent events in Egypt. For the record, I have not expressed an opinion on Egypt on this blog, and I am not going to do so on this blog. I will address something else about the Camerounian's comments.

Here is what he said:

Here is what he said:

Many people go out every year protesting for political reasons.Many die in the cause.In Egypt hundreds of people have died because they wanted one person, who might turn his back on them, to be placed back to power. I have been in protests before and I remember the dangers and group effect that make you do things you won't do if alone.I have come to see the world today different from the average person at least politically.

Some people really die protesting for what will not even help them or will not change their status.

Is it better to just ask for your bread and tea from the ruling elite and a house above your head and live peaceful till death takes us naturally? I love this life and won't go and die because i want to make it better for others because it doesn't get better at all and many people don't even get what they asked when they succeed in their protest.Nowadays I actually feel sorry for people going out and dying in protests. I will say do protest but if i sense it is getting out of hand, go back home. Dying is not worth it, what is your take?

It is a much more complicated issue than that, though, isn't it?

On the one hand, George Orwell's "Animal Farm" is a fairly accurate description of what happens following "coups", "revolutions" and other changes of government. One way or another, what comes after tends to bear a striking resemblance to what came before. All of the things that were supposedly fought against continue on, albeit under new management. And the ideologues and intellectuals that purportedly to argue in favour of changing things metamorphose into defenders of everything they previously criticized, insofar as their political faction is advantaged.

Indeed, one could argue that one of the many problems with post-colonial African countries is the "heroes of liberation" inherited all of the (undemocratic, unaccountable, unchecked) powers of the imperialists, as well as all of the coercive institutions created to impose that power on the citizenry (as well as political techniques like ethnic divide-and-rule), and have since proceeded to use that power in exactly the same manner without reform. The fact that our governments continue to take instruction from colonial-type world powers, whether directly (bilaterally) or indirectly (via institutions like the Bretton Woods agencies), only adds to the feeling that we have Black African Governor-Generals masquerading as Presidents.

On the other hand, I will admit to being tempted to tell the Camerounians that his attitude is the reason Paul Biya has been President of Cameroun for 31 years (and why Ahmadou Ahidjo was President for 22 years before Biya chased him out of the country. If he opens his mouth and says the wrong thing, Yaounde has only to threaten violent reprisal, and he will quieten down.

So, what is the answer?

I don't know. I don't think there are easy answers. I am not going to pretend to be an action hero myself.

As I said in the first paragraph, this blog post is not about Egypt.

Speaking about Nigeria, I do think that we the citizens are collectively to blame. We allow ourselves to be divided against each other so easily that we don't seem to realize that we collectively outnumber the totality of the squabbling political/economic factions that govern us. We not only outnumber them in the society at large, but we outnumber them in the Army and the Police as well.

Our overwhelming advantage was not brought to bear during the colonial period, and has not been brought to bear in the post-colonial period either. Even the soldiers and polices, who are drawn from us, from our families, have been shooting at us on behalf of governments, colonial and post-colonial alike, for more than 150 years (dating back to before the foundation of the Lagos Colony).

I am not sure any of us Nigerians would have to die to change Nigeria. We just have to collectively want it and collectively make it happen.

On the one hand, George Orwell's "Animal Farm" is a fairly accurate description of what happens following "coups", "revolutions" and other changes of government. One way or another, what comes after tends to bear a striking resemblance to what came before. All of the things that were supposedly fought against continue on, albeit under new management. And the ideologues and intellectuals that purportedly to argue in favour of changing things metamorphose into defenders of everything they previously criticized, insofar as their political faction is advantaged.

Indeed, one could argue that one of the many problems with post-colonial African countries is the "heroes of liberation" inherited all of the (undemocratic, unaccountable, unchecked) powers of the imperialists, as well as all of the coercive institutions created to impose that power on the citizenry (as well as political techniques like ethnic divide-and-rule), and have since proceeded to use that power in exactly the same manner without reform. The fact that our governments continue to take instruction from colonial-type world powers, whether directly (bilaterally) or indirectly (via institutions like the Bretton Woods agencies), only adds to the feeling that we have Black African Governor-Generals masquerading as Presidents.

On the other hand, I will admit to being tempted to tell the Camerounians that his attitude is the reason Paul Biya has been President of Cameroun for 31 years (and why Ahmadou Ahidjo was President for 22 years before Biya chased him out of the country. If he opens his mouth and says the wrong thing, Yaounde has only to threaten violent reprisal, and he will quieten down.

So, what is the answer?

I don't know. I don't think there are easy answers. I am not going to pretend to be an action hero myself.

As I said in the first paragraph, this blog post is not about Egypt.

Speaking about Nigeria, I do think that we the citizens are collectively to blame. We allow ourselves to be divided against each other so easily that we don't seem to realize that we collectively outnumber the totality of the squabbling political/economic factions that govern us. We not only outnumber them in the society at large, but we outnumber them in the Army and the Police as well.

Our overwhelming advantage was not brought to bear during the colonial period, and has not been brought to bear in the post-colonial period either. Even the soldiers and polices, who are drawn from us, from our families, have been shooting at us on behalf of governments, colonial and post-colonial alike, for more than 150 years (dating back to before the foundation of the Lagos Colony).

I am not sure any of us Nigerians would have to die to change Nigeria. We just have to collectively want it and collectively make it happen.

09 September, 2013

(+1) + (-1) = 0

Strange title for a post, right?

Someone directed me to this New York Times article on Rwandan leader Paul Kagame. Kagame isn't just favoured by the Western European and North American governments, he gets a lot of glowingly positive press from quite a few Africans. Every week, The East African publishes a regular column by Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, who functions as an uncritical, downright fawning town crier for President Kagame.

I will never pretend to know or understand Rwanda as well as a Rwandan would. I am an outsider, and will always be so.

But in the equation I used at the title of this post, and equal about of negative and positive nets to zero. If you increase the magnitude of the negative, it would move from 0 to a negative value.

I am sure I have mentioned before that I am the most politically neutral person you will ever meet. I do not support any political party or politician or political ideology. And yes, that is neutrality, as much as you will see in this world where everyone seems to have someone or something that they support, sometimes without enthusiasm and other times quite passionately.

Someone directed me to this New York Times article on Rwandan leader Paul Kagame. Kagame isn't just favoured by the Western European and North American governments, he gets a lot of glowingly positive press from quite a few Africans. Every week, The East African publishes a regular column by Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, who functions as an uncritical, downright fawning town crier for President Kagame.

I will never pretend to know or understand Rwanda as well as a Rwandan would. I am an outsider, and will always be so.

But in the equation I used at the title of this post, and equal about of negative and positive nets to zero. If you increase the magnitude of the negative, it would move from 0 to a negative value.

I am sure I have mentioned before that I am the most politically neutral person you will ever meet. I do not support any political party or politician or political ideology. And yes, that is neutrality, as much as you will see in this world where everyone seems to have someone or something that they support, sometimes without enthusiasm and other times quite passionately.

For more than 10 years, there was vicious, vicious, unbelievably vicious violence in Liberia and Sierra Leone. A proper discussion of why this came to be is too vast for a blog. Suffice to say there were many internal/domestic actors, many regional African actors, and many global/international actors who bear some degree of responsibility. It might be politically incorrect of me to say, but as citizens, we also share responsibility for watching passively as our countries collapse all around us. Collapse is never instantaneous; it always happens over a period of time long enough for us to do something to stop it.

On the list of people who are most responsible, you will find three African presidents, two of whom are dead, and one of whom is still alive. One of the dead presidents remains popular with many Africans because he is perceived to have made his country an "economic miracle" (inasmuch as it collapsed in anarchy after his death, because his was a one-man dictatorship with no institutions of substance beyond himself). The second dead president is popular with certain sections of the "Pan-Africanist" movement, because of his rhetoric in favour of a United States of Africa (inasmuch as his spent his decades in the presidency fomenting wars all over the continent). The third, still-living, still-in-power president is praised in the Western European and North American media for being a key sub-regional interlocutor, mediator and ally in terms of their security interests in the region.

What nobody ever talks about is how much responsibility the three bear for the horrors visited on Liberia and Sierra Leone. Whatever good thing they may happen to have done in there own countries, or on behalf of Western European and North American security interests (leaving aside the question of whether their interests and ours are compatible), cannot make up for what happened in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The Rwandan Genocide happened. There is a vital security interest for Rwanda in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But sometimes .... no .... very often .... no ... always in the arena of "strategic national interests", governments use a real "interest" as an excuse to do other things that have nothing to do with that "interest". And with all due respect to the fans of President Kagame, his actions in and policies toward the DR-Congo are a massive negative that outweighs whatever good he may be doing within Rwanda.

There is dispute as to how many people have died directly and indirectly because of the Congolese catastrophe. Some say the numbers in terms of "excess death" are already higher than the numbers for the Rwandan Genocide. Others say the "excess death" toll is lower than the Rwandan Genocide. But so long as the "excess death" numbers continue climbing year-after-year, this dispute may be moot.

If you've been reading this blog, you would know that I favour analytical explanations for violence in Nigeria over simply claiming one ethnic groups hates another one. As such, I want to be careful in the next thing I say, which is that the 1994 Genocide was not the first incident of Hutu-on-Tutsi, or for that matter Tutsi-on-Hutu communal violence. I would have to be a Rwandan or Burundian, with their level of knowledge of their country, to come up with an explanation for why this violence occurs, but it has happened often enough for me to say that there is no particular reason for assuming that it will not happen again.

I am not a prophet of doom ... but, as you might have noticed from reading this blog, I really dislike the way so-called "experts" analyze the continent. And I think it is rather dangerous that we Africans accept their analysis as truth.

Kagame's government is not the first government to be in power in the aftermath of one of these violent incidents. And this is not the first time that it has appeared, on the surface, that it was over and would never happen again.

The DR-Congo is a rather large place, and insofar as Rwandan policy does nothing to help the place, and plenty to harm it, Kagame is not exactly making Rwanda safer in the long-term. Maybe not even in the medium-term. Whatever the real security interests of Rwanda are, the policies of

the Kigali government are not making the region more secure or less

insecure.

To be honest, I am not entirely certain that Kagame's domestic policies are making the country safer. To what extent are things quiet because the underlying issues have been resolved, and to what extent do things simply appear to be quiet because he has established an unchallenged institutional capacity to coerce the appearance of resolution from his people?

The late President Felix Houphouet-Boigny received an even greater magnitude of positive, appreciative media support from Western Europe and North America. Within Africa, he was seen as the man responsible for what was perceived to be a miracle economy in Cote d'Ivoire. Then he died, and the people were exposed to the realities of a country where there were no real institutions beyond Houphouet-Boigny. They had no electoral system really, no judicial system, no political parties, no security system (with all due respect, their Army and Police were too small, and way too ineffectual). There was nothing. Just Houphouet-Boigny.

There are two lessons. The first is that no matter how pretty a country might look when in the grip of a one-man government, there are inherent, structural dangers to such a system, dangers that would exist even without the complication of genocide or of anarchy in a neighbouring DRC. The second lesson is the fact that praise or even criticism from the Western European and North American media does not really tell you whether or not the person they are praising is doing the right thing, or whether the person they are criticizing is doing the wrong thing. We have to step out of their centuries-long shadow, and start to ask ourselves what a proper government of an African country is supposed to look like and function like.

I know people will say that I should not be unrealistic, and that under the circumstances, this is better than the alternative .... but this is the same nonsense excuse that has been used repeatedly over the decades, and the one thing we should have learned by now is these supposedly "realistic" solutions to dilemmas end up perpetuating the very thing that the so-called "realists" think they are countering.

I just find it very hard to overlook what is happening in the DR-Congo when I read an article about how Paul Kagame is transforming Rwanda. Why does it not occur to people that events in the DR-Congo can, in the medium- to longer-term, wreck whatever Kagame builds in Rwanda in the short-term?

11 August, 2013

What We Say About Ourselves - 1

My apologies for not updating this blog in a while.

My three most recent posts have been on "propaganda" in the foreign/international media (here, here and here). It is usually not as overt as these examples, and the massaging, spinning, pointed editing and unabashed distortion of the "news" is not always done to quite that degree.

But you already knew that. Most people know "news" dissemination outlets -- be they government information ministers, mainstream media, "alternative" media, "satirists", bloggers, etc. -- try to push their viewers/listeners/readers towards adopting whatever happens to be that particular outlets' political or ideological agenda.

You also know that most people who criticize media bias, are not really criticizing media bias as an abstract concept, but are rather lambasting that part of the media (mainstream or alternative) that is not biased in favour of their agenda; such people amusingly tout equally biased outlets that happen to be biased in favour of their agendas as being more truthful.

If you are like me, and you just want to know what exactly is going on, you are out of luck.

But all those posts about media in the rest of the world are a digression from the purpose of this blog.

Frankly, we Nigerians/Africans spend too much time and energy on what is done by other peoples in their own countries. Many of us are loquacious "experts" when it comes to the minutiae of politics in the USA, Britain, France, Israel-Palestine and the Arabian Peninsula (much of this "expertise" based on dubious reports from the international media).

In the meantime:

(a) We know comparatively little about politics in the African countries that are our continental next-door neighbours.

(b) We don't know anywhere near as much as we should about other regions within our own countries.

(c) We are so powerless in the politics of our own hometowns that we cannot make the authorities do so much as clear the piles of garbage that build up on our streets.

It doesn't matter though. We know everything about USA, Britain, France and Western Asia.

While I am here, criticizing "propaganda" in the foreign media, the truth is the Nigerian and African media get their "news" of the world by culling stories from the foreign media. We get our news about the rest of Africa ... by culling stories from the foreign media.

Dangerously, our constitution-writers, media commentators, academics, intellectuals, politicians, technocrats, policy-makers, diplomats, generals and other decision-makers also tend to cull their thoughts and "analysis" of our problems, prospects and path to development from foreign sources as well. The African continent is known for self-defeating policy-making, in part because so many key decision-makers have absorbed other people's views of the African continent, and have come to the conclusion that "African strategic interests" are a set of actions and decisions that are actually in other people's strategic interests at the expense of ours.

Ultimately, we the Africans are producers of some of the world's most insidiously anti-African propaganda.

More on this in subsequent posts.

My three most recent posts have been on "propaganda" in the foreign/international media (here, here and here). It is usually not as overt as these examples, and the massaging, spinning, pointed editing and unabashed distortion of the "news" is not always done to quite that degree.

But you already knew that. Most people know "news" dissemination outlets -- be they government information ministers, mainstream media, "alternative" media, "satirists", bloggers, etc. -- try to push their viewers/listeners/readers towards adopting whatever happens to be that particular outlets' political or ideological agenda.

You also know that most people who criticize media bias, are not really criticizing media bias as an abstract concept, but are rather lambasting that part of the media (mainstream or alternative) that is not biased in favour of their agenda; such people amusingly tout equally biased outlets that happen to be biased in favour of their agendas as being more truthful.

If you are like me, and you just want to know what exactly is going on, you are out of luck.

But all those posts about media in the rest of the world are a digression from the purpose of this blog.

Frankly, we Nigerians/Africans spend too much time and energy on what is done by other peoples in their own countries. Many of us are loquacious "experts" when it comes to the minutiae of politics in the USA, Britain, France, Israel-Palestine and the Arabian Peninsula (much of this "expertise" based on dubious reports from the international media).

In the meantime:

(a) We know comparatively little about politics in the African countries that are our continental next-door neighbours.

(b) We don't know anywhere near as much as we should about other regions within our own countries.

(c) We are so powerless in the politics of our own hometowns that we cannot make the authorities do so much as clear the piles of garbage that build up on our streets.

It doesn't matter though. We know everything about USA, Britain, France and Western Asia.

While I am here, criticizing "propaganda" in the foreign media, the truth is the Nigerian and African media get their "news" of the world by culling stories from the foreign media. We get our news about the rest of Africa ... by culling stories from the foreign media.

Dangerously, our constitution-writers, media commentators, academics, intellectuals, politicians, technocrats, policy-makers, diplomats, generals and other decision-makers also tend to cull their thoughts and "analysis" of our problems, prospects and path to development from foreign sources as well. The African continent is known for self-defeating policy-making, in part because so many key decision-makers have absorbed other people's views of the African continent, and have come to the conclusion that "African strategic interests" are a set of actions and decisions that are actually in other people's strategic interests at the expense of ours.

Ultimately, we the Africans are producers of some of the world's most insidiously anti-African propaganda.

More on this in subsequent posts.

22 January, 2013

The Insidiousness of Propaganda (2)

This post continues from the one immediately prior.

I have known for decades that there is no such thing as "objective" and "unbiased" when it comes to the media. Indeed, I strive to get "news" from rival sources with contradictory biases, knowing that each side will highlight the part of the news that ties into their bias and ignore the part of the news that doesn't. Even so, I caught myself one day having a viscerally negative reaction to a politician from a foreign country (i.e. not Nigeria) after months of reading relentlessly negative portrayals of that politician from variously biased news sources from the man's home continent.

What made these sources (from the "right" and the "left") dislike the man was his contrary opinion on one specific issue on which journalists from the "right" and "left" of this particular region agreed on. The thing is, the man had every right to have that opinion, and regardless of whether I agreed with him or not, the journalists' shared position was simply an ideological opinion and not an absolute truth.

To be honest, I didn't and don't have an opinion on the man, because I do not understand the man's language and hence have never heard (or read) him expressing his opinion in his own words, from his own mouth (or pen). Everything I have ever heard or learned about him came from the mouths and pens of people who dislike him because he doesn't share their opinion. They tend to caricature him as being stupid, looking stupid and talking stupid. I always made it a point to disregard the caricaturing, but one day, in one moment, after years of reading about him in the English-language media, I looked at a picture of him and the first thing that came to mind was he looked stupid.

I instantaneously caught myself, realized that for all my efforts to block out the propaganda, I had in fact been affected by it.

This video, pulled from Youtube, discusses how journalists, politicians and the media can subtly or openly influence and manipulate citizen perceptions of other peoples.

I have known for decades that there is no such thing as "objective" and "unbiased" when it comes to the media. Indeed, I strive to get "news" from rival sources with contradictory biases, knowing that each side will highlight the part of the news that ties into their bias and ignore the part of the news that doesn't. Even so, I caught myself one day having a viscerally negative reaction to a politician from a foreign country (i.e. not Nigeria) after months of reading relentlessly negative portrayals of that politician from variously biased news sources from the man's home continent.

What made these sources (from the "right" and the "left") dislike the man was his contrary opinion on one specific issue on which journalists from the "right" and "left" of this particular region agreed on. The thing is, the man had every right to have that opinion, and regardless of whether I agreed with him or not, the journalists' shared position was simply an ideological opinion and not an absolute truth.

To be honest, I didn't and don't have an opinion on the man, because I do not understand the man's language and hence have never heard (or read) him expressing his opinion in his own words, from his own mouth (or pen). Everything I have ever heard or learned about him came from the mouths and pens of people who dislike him because he doesn't share their opinion. They tend to caricature him as being stupid, looking stupid and talking stupid. I always made it a point to disregard the caricaturing, but one day, in one moment, after years of reading about him in the English-language media, I looked at a picture of him and the first thing that came to mind was he looked stupid.

I instantaneously caught myself, realized that for all my efforts to block out the propaganda, I had in fact been affected by it.

This video, pulled from Youtube, discusses how journalists, politicians and the media can subtly or openly influence and manipulate citizen perceptions of other peoples.

The Insidiousness of Propaganda (1)

I prefer not to copy and paste entire articles from newspapers' websites. Many people earn their living through journalism. Heaven knows jobs are scarce everywhere in the world, and that formal sector jobs are especially scarce in the Federal Republic of Nigeria. We have neither Welfare nor the Dole, so one shouldn't make it more difficult for people to support themselves, their families and their retirement through honest work.

Having said that, there is a point I want to make, and in order to make that point, I have to be sure you read the entirety of the article I am about to post here. I don't read the newspaper from which it was sourced, but my attention was drawn to it by a writer on another website.

Having said that, there is a point I want to make, and in order to make that point, I have to be sure you read the entirety of the article I am about to post here. I don't read the newspaper from which it was sourced, but my attention was drawn to it by a writer on another website.

This is how racism takes root

The different ways the media covered two cases of men grooming children for sex show how shockingly easy it is to demonise a whole community

Joseph Harker

The Guardian, Sunday 22 July 2012 20.30 BST

By now surely everyone knows the case of the eight men convicted of picking vulnerable underage girls off the streets, then plying them with drink and drugs before having sex with them. A shocking story. But maybe you haven't heard. Because these sex assaults did not take place in Rochdale, where a similar story led the news for days in May, but in Derby earlier this month. Fifteen girls aged 13 to 15, many of them in care, were preyed on by the men. And though they were not working as a gang, their methods were similar – often targeting children in care and luring them with, among other things, cuddly toys. But this time, of the eight predators, seven were white, not Asian. And the story made barely a ripple in the national media.

Of the daily papers, only the Guardian and the Times reported it. There was no commentary anywhere on how these crimes shine a light on British culture, or how middle-aged white men have to confront the deep flaws in their religious and ethnic identity. Yet that's exactly what played out following the conviction in May of the "Asian sex gang" in Rochdale, which made the front page of every national newspaper. Though analysis of the case focused on how big a factor was race, religion and culture, the unreported story is of how politicians and the media have created a new racial scapegoat. In fact, if anyone wants to study how racism begins, and creeps into the consciousness of an entire nation, they need look no further.

Imagine you were living in a town of 20,000 people – the size of, say, Penzance in Cornwall – and one day it was discovered that one of its residents had been involved in a sex crime. Would it be reasonable to say that the whole town had a cultural problem, that it needed to address the scourge – that anyone not doing so was part of a "conspiracy of silence"? But the intense interest in the Rochdale story arose from a January 2011 Times "scoop" that was based on the conviction of at most 50 British Pakistanis out of a total UK population of 1.2 million, just one in 24,000: one person per Penzance.

Make no mistake, the Rochdale crimes were vile, and those convicted deserve every year of their sentences. But where, amid all the commentary, was the evidence that this is a racial issue; that there's something inherently perverted about Muslim or Asian culture?

Even the Child Protection and Online Protection Centre (Ceop), which has also studied potential offenders who have not been convicted, has only identified 41 Asian gangs (of 230 in total) and 240 Asian individuals – and they are spread across the country. But, despite this, a new stereotype has taken hold: that a significant proportion of Asian men are groomers (and the rest of their communities know of it and keep silent).

But if it really is an "Asian" thing, how come Indians don't do it? If it's a "Pakistani" thing, how come an Afghan was convicted in the Rochdale case? And if it's a "Muslim" thing, how come it doesn't seem to involve anyone of African or Middle Eastern origin? The standard response to anyone who questions this is: face the facts, all those convicted in Rochdale were Muslim. Well, if one case is enough to make such a generalisation, how about if all the members of a gang of armed robbers were white; or cybercriminals; or child traffickers? (All three of these have happened.) Would we be so keen to "face the facts" and make it a problem the whole white community has to deal with? Would we have articles examining what it is about Britishness or Christianity or Europeanness, that makes people so capable of such things?

In fact, Penzance had not just one paedophile, but a gang of four. They abused 28 girls, some as young as five, and were finally convicted two years ago. All were white. And last month, at a home affairs select committee, deputy children's commissioner Sue Berelowitz quoted a police officer who had told her that "there isn't a town, village or hamlet in which children are not being sexually exploited".

Whatever the case, we know that abuse of white girls is not a cultural or religious issue because there is no longstanding history of it taking place in Asia or the Muslim world.

How did middle-aged Asian men from tight-knit communities even come into contact with white teenage girls in Rochdale? The main cultural relevance in this story is that vulnerable, often disturbed, young girls, regularly out late at night, often end up in late-closing restaurants and minicab offices, staffed almost exclusively by men. After a while, relationships build up, with the men offering free lifts and/or food. For those with a predatory instinct, sexual exploitation is an easy next step. This is an issue of what men can do when away from their own families and in a position of power over badly damaged young people.

It's a story repeated across Britain, by white and other ethnic groups: where the opportunity arises, some men will take advantage. The precise method, and whether it's an individual or group crime, depends on the particular setting – be they priests, youth workers or networks on the web.

Despite all we know about racism, genocide and ethnic cleansing, the Rochdale case showed how shockingly easy it is to demonise a community. Before long, the wider public will believe the problem is endemic within that race/religion, and that anyone within that group who rebuts the claims is denying this basic truth. Normally, one would expect a counter-argument to force its way into the discussion. But in this case the crimes were so horrific that right-thinking people were naturally wary of being seen to condone them. In fact, the reason I am writing this is that I am neither Asian nor Muslim nor Pakistani, so I cannot be accused of being in denial or trying to hide a painful truth. But I am black, and I know how racism works; and, more than that, I have a background in maths and science, so I know you can't extrapolate a tiny, flawed set of data and use it to make a sweeping generalisation.

I am also certain that, if the tables were turned and the victims were Asian or Muslim, we would have been subjected to equally skewed "expert" commentary asking: what is wrong with how Muslims raise girls? Why are so many of them on the streets at night? Shouldn't the community face up to its shocking moral breakdown?

While our media continue to exclude minority voices in general, such lazy racial generalisations are likely to continue. Even the story of a single Asian man acting alone in a sex case made the headlines. As in Derby this month, countless similar cases involving white men go unreported.

We have been here before, of course: in the 1950s, West Indian men were labelled pimps, luring innocent young white girls into prostitution. By the 1970s and 80s they were vilified as muggers and looters. And two years ago, Channel 4 ran stories, again based on a tiny set of data, claiming there was an endemic culture of gang rape in black communities. The victims weren't white, though, so media interest soon faded. It seems that these stories need to strike terror in the heart of white people for them to really take off.

What is also at play here is the inability of people, when learning about a different culture or race, to distinguish between the aberrations of a tiny minority within that group, and the normal behaviour of a significant section. Some examples are small in number but can be the tip of a much wider problem: eg, knife crime, which is literally the sharp end of a host of problems affecting black communities ranging from family breakdown, to poverty, to low school achievement and social exclusion.

But in Asia, Pakistan or Islam there is no culture of grooming or sex abuse – any more than there is anywhere else in the world – so the tiny number of cases have no cultural significance. Which means those who believe it, or perpetuate it, are succumbing to racism, much as they may protest. Exactly the same mistake was made after 9/11, when the actions of a tiny number of fanatics were used to cast aspersions against a 1.5 billion-strong community worldwide. Motives were questioned: are you with us or the terrorists? How fundamental are your beliefs? Can we trust you?

Imagine if, after Anders Breivik's carnage in Norway last year, which he claimed to be in defence of the Christian world, British people were repeatedly asked whether they supported him? Lumped together in the same white religious group as the killer and constantly told they must renounce him, or explain why we should believe that their type of Christianity – even if they were non-believers – is different from his. "It's nothing to do with me", most people would say. But somehow that answer was never good enough when given by Muslims over al-Qaida. And this hectoring was self-defeating because it caused only greater alienaton and resentment towards the west and, in particular, its foreign policies.

Ultimately, the urge to vilify groups of whom we know little may be very human, and helps us bond with those we feel are "like us". But if we are going to deal with the world as it is, and not as a cosy fantasyland where our group is racially and culturally supreme, we have to recognise when sweeping statements are false.

And if we truly care about the sexual exploitation of girls, we need to know that we must look at all communities, across the whole country, and not just at those that play to a smug sense of superiority about ourselves.

08 January, 2013

Central African Republic and Regional Security

This blog focuses mostly on the reform, restructuring and transformation of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, so there haven't really been that many posts on pan-continental issues.

One could argue, I suppose, that matters that affect Nigeria are by definition matters of importance to the continent. What is indisputable is we Africans tend to pay too much attention to political matters in Western Europe (particularly France and the United Kingdom), North America (particularly the USA) and Western Asia ....

.... and too little attention to matters occurring in other African countries or regions.

The quality of information available, to the extent that we do follow events in our neighbourhoods (or even in our own countries) is questionable. We get a lot of "news", "analysis" and "discourse" from foreign (i.e. non-African sources) or from domestic sources that have been influenced by foreign sources (and are often led by managers or journalists who were educated abroad, or educated at home by professors who were educated abroad). What is presented as the consensus opinion about an issue is something that sounds like what an outsider would come up with from a brief glance at the surface, and does not sound like the product of a person or people who truly understand what is going on, or even just have the complete set of basic facts about the what, why, who and how.

But I digress.

Like I said, I don't write too often about pan-continental issues except insofar as the issues affecting Nigeria are similar to the issues affecting other countries, or insofar as anything that affects Nigeria is important to Africa at large.

I did, however, write this post about African governments that disguise and propagandize their efforts at undemocratic self-preservation against the will of their citizens by purporting to be opposed to "unconstitutional changes of government" (i.e. coups).

Sometime in December, 2012, elements of three Central African Republic rebels groups united to form a new, larger rebel alliance. This Alliance proved so successful so quickly that it was in position to overrun the capital, Bangui, in a short time. The USA shut down its embassy, and President Bozize called on his neighbours (and on France), to save his government. Bozize is desperate to agree to offer to share power with the rebels (as though he couldn't have done this a long time ago).

France and the United States are doing the usual thing of officially and publicly professing their political non-involvement, calling for peaceful resolution, etc, etc. As to what they are or are not doing secretly, practically and unofficially, one way or the other, we will only know after we see the results.

African countries have rushed to prop up Bozize's regime. His closest ally is the government of Chad, who rely on him to not support Chadian rebels the way other C.A.R. governments have done; Chadian President Idris Deby pledged to send up to 2,000 soldiers to bolster Bozize. Support also came from Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon and Cameroun. The hastily-assembled force currently on the ground to protect Bangui from the rebel alliance includes: Chad (400 troops), South Africa (200 troops), Cameroun (120), Gabon (120), and Congo-Brazzaville (120).

Look, if I lived in Bangui or had family living in Bangui, I would want to do anything to avoid the city becoming a combat zone ... again.

I understand that motivation. I have had family in a war zone before. And not just once.

However, the preservation of the Bozize Regime does absolutely nothing to fix the chronic and persistent problems (including a near-constant security crisis) that have plagued the C.A.R. for decades.

Mind you, allowing the rebels to sweep him out of office wouldn't fix the problem either.

This is my problem with Nigerian politics. It is also my problem with African politics. And while I do not have any particular visceral reaction towards the domestic politics of countries in the rest of the world, one notices the same pattern in that citizens are always presented with a situation where none of the choices they are allowed to make is a choice that would actually fix the problems they want to have fixed. You always get a choice between nothing you want, and are expected to choose the party or person that you dislike but dislike less than you dislike the other person or parties.

For other parts of the world, outside of Africa, the deliberately restricted scope of political choice is not that big of a problem, at least not at present. For example, I suppose the average Japanese person feels some sort of effect from the fact that neither the DPJ or LDP has any answers to Japan's 20-year economic questions, but none of them suffers in the way that a citizen of the C.A.R. suffers due to the absence of a political choice representing a solution to their dillenma.

Presented with this reality, a lot of people's reactions boil down to "don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good" or "don't let the good be the enemy of the better", but these so-called "solutions" to the problems of countries like C.A.R. are themselves no more than lubrication for the continuation of all of the basic problems. This isn't a case of opposing an improvement in the name of perfection, but is more a case of asking why we are fanning the flames when we should be putting them out.

Remember what I said about understanding how someone who lived in Bangui or had family there would want to avoid the city becoming a warzone? If I lived in Bangui or had family there, I would have experienced this same exact anxiety, trepidation and fear so many times over the last 50 years that I would be sick and tired of it, and would be wondering why we just keep lubricating the continuation of the never-ending conflicts. Being told that soldiers from the rest of Africa are here to make sure the same thing continues happening decades in the future would prompt me to join those people who make perilous journeys across the Sahara just to get to anywhere other than their own countries.

None of these things solve the problem.

It reminds me of a semi-acquaintance of mine, who supports the idea of sending Nigerian soldiers to go and fight in Mali. According to him, if they don't go, it would mean the forces holding the north of Mali would be able to send weapons to the insurgents behind a wave of violence in Nigeria.

But this is warped thinking.

There is nothing that Nigerian troops could or would do in Mali that would stop the flow of weapons to Nigerian insurgent groups. Even if Nigeria single-handedly conquered all of Mali, planted the Nigerian flag, and declared Mali to be the 37th State of Nigeria, all of the insurgent and militant groups in Nigeria would still be getting weapons. I wrote an essay nine years ago, ahead of the 2003 Elections, that complained about the Nigerian Federal Government's inability to do anything about the smuggling of heavy weapons into the country, among other complaints. Back then, everyone thought Mali was an African success story, rating them (along with Ghana) among the most democratic and well-governed countries on the continent.

Mind you, the fact that I wrote the essay in 2003 does not mean the problem of insurgent/militant groups' access to heavy weaponry started in 2003. On the contrary, it was already a long-standing problem by then.

Look, sending Nigerian troops to Darfur has not brought peace to Darfur, nor has it done anything to stop the flow of weapons across African borders in general, or in particular the smuggling of heavy weapons into Nigeria. Nigerian soldiers have died in Darfur, though nowhere near as many as died in Liberia and Sierra Leone. We've also lost soldiers in Somalia in the early 1990s without there being an appreciable difference in the levels of violence for another 20+ years.

Sierra Leone and Liberia are usually presented as examples of the success of this kind of intervention, but both countries remain fragile in security terms. If anything the "peace" has provided a veil behind which the same forces that created problems in Sierra Leone and Liberia have expanded to affect Cote d'Ivoire (especially), as well as Guinea and Guinea-Bissau to a certain extent. Weapons, armed persons and (in the case of Guinea-Bissau) globally proscribed narcotic products, continue to move across the borders of the wider Mano River Region with ease.

I am not being a pessimist. What I am doing is trying to promote some kind of proactive thinking. The truth of the matter is the Mano River Region is not so much at peace as it is in a sort of inter-war lull before the next outbreak, wherever that outbreak might be.

Indeed, proactive thinking is clearly nonexistent in these many crises. Whatever one may think of the prior government of Libya (or even for that matter of the current government of Libya), the NATO countries' actions in Libya have resulted in something of a catastrophe for Mali and West Africa, and nobody foresaw the possibility or did anything to ward it off or to contain it once it became clear what was going to happen.

I love the Federal Republic of Nigeria, but I hate the "Giant of Africa" tag that our political leaders like to bandy about. Self-hype is no substitute for basic, simple proactive thinking about strategic interests in our immediate neighbourhood, and self-praise does not hide from anyone the fact that we have little or no influence on events as near to us as Chad, Equatorial Guinea and Niger Republic, much less further afield. We watched what happened in Libya as spectators, watched the fallout as spectators. We are now scrambling to send soldiers to Mali because other people have told us to do so, and not because we have carefully considered what we have to do to finally fix underlying problems in our country and our region. These "experts" whose requests we are obeying are the same people whose "expertise" created the problem in the first place.

You are probably wondering when I will get to a suggested solution, as opposed to a long litany of complaints.

But that is just it. The name of this blog is "For A New Federal Republic", and it is sub-titled "Reform, Restructure and Transform" the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

We can't keep things in Nigeria the way they are, and then deceive ourselves that sending soldiers to this or that country will fix the problem with security in our country and in our neighbourhood.

We can't fight to keep the Bozize Government in place, essentially keeping everything in the C.A.R. fundamentally the same as it has always been, and deceive ourselves that we have brought peace to the place.

There is so much that is fundamentally problematic about the nature of the politics and economies of Nigeria and its neighbourhood and all of it has to be fixed, or we will remain excessively and unnecessarily prone to these type of problems.

Indeed, one can argue that the biggest reason why countries like the C.A.R. cannot reach their economic potential is Nigeria, the country that should be the engine driving the region, is doing everything in the world to AVOID achieving its economic potential.

You cannot correct this by sending soldiers here, there and everywhere across Africa.

We must REFORM, RESTRUCTURE AND TRANSFORM the FEDERAL REPUBLIC.

One could argue, I suppose, that matters that affect Nigeria are by definition matters of importance to the continent. What is indisputable is we Africans tend to pay too much attention to political matters in Western Europe (particularly France and the United Kingdom), North America (particularly the USA) and Western Asia ....

.... and too little attention to matters occurring in other African countries or regions.

The quality of information available, to the extent that we do follow events in our neighbourhoods (or even in our own countries) is questionable. We get a lot of "news", "analysis" and "discourse" from foreign (i.e. non-African sources) or from domestic sources that have been influenced by foreign sources (and are often led by managers or journalists who were educated abroad, or educated at home by professors who were educated abroad). What is presented as the consensus opinion about an issue is something that sounds like what an outsider would come up with from a brief glance at the surface, and does not sound like the product of a person or people who truly understand what is going on, or even just have the complete set of basic facts about the what, why, who and how.

But I digress.

Like I said, I don't write too often about pan-continental issues except insofar as the issues affecting Nigeria are similar to the issues affecting other countries, or insofar as anything that affects Nigeria is important to Africa at large.

I did, however, write this post about African governments that disguise and propagandize their efforts at undemocratic self-preservation against the will of their citizens by purporting to be opposed to "unconstitutional changes of government" (i.e. coups).

Sometime in December, 2012, elements of three Central African Republic rebels groups united to form a new, larger rebel alliance. This Alliance proved so successful so quickly that it was in position to overrun the capital, Bangui, in a short time. The USA shut down its embassy, and President Bozize called on his neighbours (and on France), to save his government. Bozize is desperate to agree to offer to share power with the rebels (as though he couldn't have done this a long time ago).

France and the United States are doing the usual thing of officially and publicly professing their political non-involvement, calling for peaceful resolution, etc, etc. As to what they are or are not doing secretly, practically and unofficially, one way or the other, we will only know after we see the results.

African countries have rushed to prop up Bozize's regime. His closest ally is the government of Chad, who rely on him to not support Chadian rebels the way other C.A.R. governments have done; Chadian President Idris Deby pledged to send up to 2,000 soldiers to bolster Bozize. Support also came from Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon and Cameroun. The hastily-assembled force currently on the ground to protect Bangui from the rebel alliance includes: Chad (400 troops), South Africa (200 troops), Cameroun (120), Gabon (120), and Congo-Brazzaville (120).

Look, if I lived in Bangui or had family living in Bangui, I would want to do anything to avoid the city becoming a combat zone ... again.

I understand that motivation. I have had family in a war zone before. And not just once.

However, the preservation of the Bozize Regime does absolutely nothing to fix the chronic and persistent problems (including a near-constant security crisis) that have plagued the C.A.R. for decades.

Mind you, allowing the rebels to sweep him out of office wouldn't fix the problem either.

This is my problem with Nigerian politics. It is also my problem with African politics. And while I do not have any particular visceral reaction towards the domestic politics of countries in the rest of the world, one notices the same pattern in that citizens are always presented with a situation where none of the choices they are allowed to make is a choice that would actually fix the problems they want to have fixed. You always get a choice between nothing you want, and are expected to choose the party or person that you dislike but dislike less than you dislike the other person or parties.

For other parts of the world, outside of Africa, the deliberately restricted scope of political choice is not that big of a problem, at least not at present. For example, I suppose the average Japanese person feels some sort of effect from the fact that neither the DPJ or LDP has any answers to Japan's 20-year economic questions, but none of them suffers in the way that a citizen of the C.A.R. suffers due to the absence of a political choice representing a solution to their dillenma.

Presented with this reality, a lot of people's reactions boil down to "don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good" or "don't let the good be the enemy of the better", but these so-called "solutions" to the problems of countries like C.A.R. are themselves no more than lubrication for the continuation of all of the basic problems. This isn't a case of opposing an improvement in the name of perfection, but is more a case of asking why we are fanning the flames when we should be putting them out.

Remember what I said about understanding how someone who lived in Bangui or had family there would want to avoid the city becoming a warzone? If I lived in Bangui or had family there, I would have experienced this same exact anxiety, trepidation and fear so many times over the last 50 years that I would be sick and tired of it, and would be wondering why we just keep lubricating the continuation of the never-ending conflicts. Being told that soldiers from the rest of Africa are here to make sure the same thing continues happening decades in the future would prompt me to join those people who make perilous journeys across the Sahara just to get to anywhere other than their own countries.

None of these things solve the problem.

It reminds me of a semi-acquaintance of mine, who supports the idea of sending Nigerian soldiers to go and fight in Mali. According to him, if they don't go, it would mean the forces holding the north of Mali would be able to send weapons to the insurgents behind a wave of violence in Nigeria.

But this is warped thinking.

There is nothing that Nigerian troops could or would do in Mali that would stop the flow of weapons to Nigerian insurgent groups. Even if Nigeria single-handedly conquered all of Mali, planted the Nigerian flag, and declared Mali to be the 37th State of Nigeria, all of the insurgent and militant groups in Nigeria would still be getting weapons. I wrote an essay nine years ago, ahead of the 2003 Elections, that complained about the Nigerian Federal Government's inability to do anything about the smuggling of heavy weapons into the country, among other complaints. Back then, everyone thought Mali was an African success story, rating them (along with Ghana) among the most democratic and well-governed countries on the continent.

Mind you, the fact that I wrote the essay in 2003 does not mean the problem of insurgent/militant groups' access to heavy weaponry started in 2003. On the contrary, it was already a long-standing problem by then.

Look, sending Nigerian troops to Darfur has not brought peace to Darfur, nor has it done anything to stop the flow of weapons across African borders in general, or in particular the smuggling of heavy weapons into Nigeria. Nigerian soldiers have died in Darfur, though nowhere near as many as died in Liberia and Sierra Leone. We've also lost soldiers in Somalia in the early 1990s without there being an appreciable difference in the levels of violence for another 20+ years.

Sierra Leone and Liberia are usually presented as examples of the success of this kind of intervention, but both countries remain fragile in security terms. If anything the "peace" has provided a veil behind which the same forces that created problems in Sierra Leone and Liberia have expanded to affect Cote d'Ivoire (especially), as well as Guinea and Guinea-Bissau to a certain extent. Weapons, armed persons and (in the case of Guinea-Bissau) globally proscribed narcotic products, continue to move across the borders of the wider Mano River Region with ease.

I am not being a pessimist. What I am doing is trying to promote some kind of proactive thinking. The truth of the matter is the Mano River Region is not so much at peace as it is in a sort of inter-war lull before the next outbreak, wherever that outbreak might be.

Indeed, proactive thinking is clearly nonexistent in these many crises. Whatever one may think of the prior government of Libya (or even for that matter of the current government of Libya), the NATO countries' actions in Libya have resulted in something of a catastrophe for Mali and West Africa, and nobody foresaw the possibility or did anything to ward it off or to contain it once it became clear what was going to happen.

I love the Federal Republic of Nigeria, but I hate the "Giant of Africa" tag that our political leaders like to bandy about. Self-hype is no substitute for basic, simple proactive thinking about strategic interests in our immediate neighbourhood, and self-praise does not hide from anyone the fact that we have little or no influence on events as near to us as Chad, Equatorial Guinea and Niger Republic, much less further afield. We watched what happened in Libya as spectators, watched the fallout as spectators. We are now scrambling to send soldiers to Mali because other people have told us to do so, and not because we have carefully considered what we have to do to finally fix underlying problems in our country and our region. These "experts" whose requests we are obeying are the same people whose "expertise" created the problem in the first place.

You are probably wondering when I will get to a suggested solution, as opposed to a long litany of complaints.

But that is just it. The name of this blog is "For A New Federal Republic", and it is sub-titled "Reform, Restructure and Transform" the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

We can't keep things in Nigeria the way they are, and then deceive ourselves that sending soldiers to this or that country will fix the problem with security in our country and in our neighbourhood.

We can't fight to keep the Bozize Government in place, essentially keeping everything in the C.A.R. fundamentally the same as it has always been, and deceive ourselves that we have brought peace to the place.

There is so much that is fundamentally problematic about the nature of the politics and economies of Nigeria and its neighbourhood and all of it has to be fixed, or we will remain excessively and unnecessarily prone to these type of problems.

Indeed, one can argue that the biggest reason why countries like the C.A.R. cannot reach their economic potential is Nigeria, the country that should be the engine driving the region, is doing everything in the world to AVOID achieving its economic potential.

You cannot correct this by sending soldiers here, there and everywhere across Africa.

We must REFORM, RESTRUCTURE AND TRANSFORM the FEDERAL REPUBLIC.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)