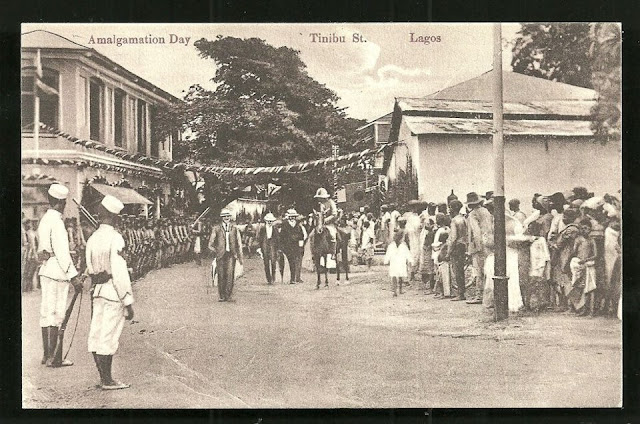

Amalgamation Day in Lagos, 1914

24 November, 2009

11 November, 2009

Raindrops make mighty rivers

As citizens, we Nigerians complain about a lot of things. Usually we externalize the blame, point a finger at "our leaders", at "XYZ ethnic group or region", at something other than ourselves. Sometimes we insist the very existence of "Nigeria" is to blame for our perceived woes; holding the amalgamation to blame is an indirect way of blaming every other ethnic group for allegedly bringing your own group down (not to mention an indirect way of calling for a break-up of the federal republic).

The truth is Nigeria is a river, and we the people are the raindrops that ultimately make up the river called Nigeria. All the individual decisions we make, and actions we take, collectively create the pool of our shared outcomes, positive and negative.

I have noticed something that bothers me.

When we Nigerians discuss our issues in a broad, generalized sense, we seem to properly identify problems, prospects and solutions, and to fervently support the search for optimality in all of our affairs as a society. But when it gets down to the hard specifics of deciding and acting, a strange metamorphosis takes place, and the very same people start defending and advocating the very things (people, decisions, actions, choices, systems, institutions, frameworks) that create and sustain the very problems they otherwise complain about. And where assertions of support for optimality never proceed beyond the level of verbal/rhetorical insistence, the protection of the sources of our problem can get stringent, bellicose, and even violent.

To some degree we are afraid of the unknown. The system may be broken, but it is a system we understand. Most of us have (following great struggle) found niches within the system, and are able to support ourselves and our families to the best of our abilities within the system. And as much as we realize the system is limiting the horizon for ourselves and our children, we are afraid that we might not find a place in the new, improved system (particularly since our survival skills are adapted to the current system, and may or may not be relevant to the new one).

To some degree, we defend the status quo because we do not see any worthwhile alternative. If you lived in the First Republic, and all of the major and minor parties are either ethnic blocs or regional pressure groups, you really don't have a choice but to vote for your ethnic bloc or your regional pressure group. No seriously, what would be the point of voting in another party whose official or unoffical goal is the advancement of another ethnic bloc or regional agenda? The fact that your own ethnic bloc or regional group is as corrupt, waste-prone, autocratic, antidemocatic, police-misusing, and minority-oppressing as its rivals does not have much of an impact on your decision -- you either pick that group or no group, if for nothing other than the sense of self-defence that is created within ethnic/regional blocs when they perceive the other ethnic/regional blocs to be maneuvring to control the central government.

But I don't really want to take up too much space with this blog post. I am not really in a mood to delve deeper into this issue.

What motivated me to mention it is the many weeks of discussion I witnessed and participated in on a Nigerian online discussion forum. The topic was Adokie Amiesimaka's accusation of cheating levelled against the Nigerian (Under-17) Eaglets team at the recent FIFA Under-17 world championships hosted by Nigeria.

It is not my intention here to discuss the substance of Adokiye's allegation. Rather there is something else that caught my attention in the arguments that pit dozens of Nigerians against each other on that discussion forum.

What caught my intention is the number of people who SUPPORTED age-cheating. Don't misunderstand me. I am not saying they agreed that there was age-cheating. In fact they insisted no such thing had happened. That was not what bothered me.

What bothered me is their declaration that even if age-cheating existed, Adokiye should not have said anything about it. They said he was unpatriotic to try to expose it. They questioned his motives, and insisted that if he had bad motives, then we shouldn't listen to his allegation even if it was true. They said life was hard for young men in Nigeria, and so if they had to age-cheat to make it out, we should not pour sand in their garri (a Nigerian phrase that roughly translates as spoiling a good thing for them). They said every team age-cheated, and that we had to age-cheat to keep up with them. And they said (and this was really perplexing) that if you support the SENIOR Eagles team, then you cannot criticize age-cheating at the junior levels because (wait till you hear this) the senior team players were guilty too! Yes, they insisted you must boycott all of Nigerian football if you think we shouldn't age-cheat at the youth levels.

Again, none of this proves we do or did age-cheat.

In fact I want to make clear that I am not saying we do or did (nor am I saying we don't or didn't). You see, that ceased to be important to me, as I watched a raging argument in which a majority of the discussants DEFENDED age-cheating as a concept, regardless of whether we do it or not.

The odd thing is this argument raged in the two weeks before our make-or-break World Cup qualifier away at Kenya, which (along with the result between Tunisia and Mozambique in Maputo) would decide whether we qualified for the 2010 World Cup.

The same people who were gladly defending age-cheating would have attacked, trashed and bashed the Nigerian Football Federation, the manager Amodu Shuaibu, and the Eagles' players if we had not qualified for the World Cup. They would have raged and railed, wondered why bad things always happen to Nigeria, called the country all sorts of horrible names, claimed (with inferiority complexes) that Ghana is so much better at electricity, football, blah, blah, blah.

Now there are many things that contribute toward ending up with a national team that is not dominant, and that has to struggle mightily where others (e.g. Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire in the 2010 qualifiers) sail more smoothly. Indeed, every team, even the good ones, goes through a cycle that resembles the sine and cosine curves -- sometimes you are up, sometimes you are down (Ghana just emerged 3 years ago from an extended period of being down).

Still, the way we manage our football at the grassroots and youth levels are part and parcel of the wider picture of dysfunction in Nigerian football. It is both hypocritical and (more importantly) self-defeating to support that, while complaining that our League, our senior national team, and our current international "stars" are not meeting your lofty expectation. You cannot plant pawpaw and harvest yam. Actually in this case, we are not planting anything at all, but are somehow expecting a bumper harvest, and (worst of all) proceed to complain, whine, bitch and moan when no such bountiful harvest occurs.

Seriously, how can you expect any output at all (even electricity generation) to come out optimal, when the input is consistently suboptimal? If you support the input, fine, that is your right, but don't then join me to complain about the output.

Many of those supporting age-cheating claimed Brazil did the same thing. Mind you, there were other countries they mentioned, but the tendency of comparing ourselves to Brazil in football (the "we produced abundant talent, only matched by Brazil" myth) makes them a very apt example to use to counter those who advocate self-defeating behaviour.

I have watched a documentary film crew go to the grassroots children's football club where Brazilian international Kaka got his start. We all knew what Ronaldinho could do while he was still at Gremio, and were thrilled by Robinho while still at Santos. There is no comparison in Nigeria. It is not just the fact that the histories of "young" players are shrouded in mystery, rumour and innuendo, but the League itself can not be compared to the Brazilian league.

There was a time in life that I stopped taking our age-restricted successes seriously. What little regard I had for them quenched after our success at the age-restricted 1996 Atlanta Olympics. We won that tournament using our de facto national team (minus Finidi), comprising 1994 World Cup and Nations Cup veterans, players from the Under-17 triump in 1993, and a sprinkling of others (notably Victor Ikpeba, from the 1989 Under-17 team).

We beat Brazil (yes, them, I bet you know where this is going) in the semifinals of the 1996 Olympics, in one of the greatest comebacks in our history. That Brazilian team, and those Brazilian players, went on to make it to the final of the 1998 World Cup, went on to WIN the 2002 World Cup, and quite a few of them were still around and kicking when Brazil made it as far as the final eight in 2006.

By contrast, the 1996 Nigerian Olympians, heroes of the nation went on to ..... well, there were a lot of blowout losses in 1998, most significantly to Denmark in 1998, and a general continuation of the 15 years of decline that began in 1994 and continued up till 2008. And it is not yet uhuru (permit me to misuse the term) in 2009, though our qualification for the World Cup could turn out to be the first spark of the revival.

One team in that 1996 semifinal was around the starting point of an upward growth in their developmetnal process, while the other team was at the height of its abilities (remember many of them had won the 1994 Nations Cup).

I will leave it at that. It is not my thesis that we are age-cheats. It is my thesis that we cannot point to Brazil, claim (without proof) that they age-cheat, and then insist that if they do it, we can do it too. Haba, the Brazilians have a football system that produces world champions, world players of the year, and some of the best players in the history of football, on a continuous and consistent basis. To point to them, and say that they are proof that it is okay for us to do the wrong thing, the stupid thing, the self-defeating thing, is insane.

In fact, we shouldn't compare ourselves to ANYBODY, successful or not. The question should be, "Does it work for Nigeria? Does it achieve Nigeria's goals?" If your goal is endlessly winning kiddie tournaments, that is one thing, but if you are looking to be a long-term, permanent, continuous WORLD POWER, then you cannot possibly bring yourself to support the continued absence of the necessary structures and foundations.

But I am (as always) starting to digress.

The point I am making is that for all our complaining about issues, we are often the footsoldiers who fight to protect, defend, sustain and continue the exact things that produce the outcomes we complain about.

In fact, that is why we have "bad leaders". These so-called leaders were born into the same families as the rest of us, into the same lives we all lead, except some quirk of fate gave them a chance to step into leadership. And you know what? The things they do once in office are the same things too many of the rest of us would do if we got that same chance. Far too many of us spend our days hoping and praying for the chance to do exactly what "they" are doing.

But then we complain when the persistence of such decision-making leads to problematic output and negative outcomes.

It is too difficult to try to change all of Nigeria at once. By contrast, we can all change ourselves as individuals, which would have the effect of changing all of Nigeria.

The thing is, it has to be in the context of a revolution, because we all have to do it at the same time. If only one person changes, and everyone else remains the same, then he or she will simply lose out in the vicious competition for survival under the current system. This is the fear that keeps Nigeria from reform, transformation and substantive change -- the fear that if I or you change alone as individuals, no one else will, and the only result would be the loss of our individual niche in the system.

The truth is Nigeria is a river, and we the people are the raindrops that ultimately make up the river called Nigeria. All the individual decisions we make, and actions we take, collectively create the pool of our shared outcomes, positive and negative.

I have noticed something that bothers me.

When we Nigerians discuss our issues in a broad, generalized sense, we seem to properly identify problems, prospects and solutions, and to fervently support the search for optimality in all of our affairs as a society. But when it gets down to the hard specifics of deciding and acting, a strange metamorphosis takes place, and the very same people start defending and advocating the very things (people, decisions, actions, choices, systems, institutions, frameworks) that create and sustain the very problems they otherwise complain about. And where assertions of support for optimality never proceed beyond the level of verbal/rhetorical insistence, the protection of the sources of our problem can get stringent, bellicose, and even violent.

To some degree we are afraid of the unknown. The system may be broken, but it is a system we understand. Most of us have (following great struggle) found niches within the system, and are able to support ourselves and our families to the best of our abilities within the system. And as much as we realize the system is limiting the horizon for ourselves and our children, we are afraid that we might not find a place in the new, improved system (particularly since our survival skills are adapted to the current system, and may or may not be relevant to the new one).

To some degree, we defend the status quo because we do not see any worthwhile alternative. If you lived in the First Republic, and all of the major and minor parties are either ethnic blocs or regional pressure groups, you really don't have a choice but to vote for your ethnic bloc or your regional pressure group. No seriously, what would be the point of voting in another party whose official or unoffical goal is the advancement of another ethnic bloc or regional agenda? The fact that your own ethnic bloc or regional group is as corrupt, waste-prone, autocratic, antidemocatic, police-misusing, and minority-oppressing as its rivals does not have much of an impact on your decision -- you either pick that group or no group, if for nothing other than the sense of self-defence that is created within ethnic/regional blocs when they perceive the other ethnic/regional blocs to be maneuvring to control the central government.

But I don't really want to take up too much space with this blog post. I am not really in a mood to delve deeper into this issue.

What motivated me to mention it is the many weeks of discussion I witnessed and participated in on a Nigerian online discussion forum. The topic was Adokie Amiesimaka's accusation of cheating levelled against the Nigerian (Under-17) Eaglets team at the recent FIFA Under-17 world championships hosted by Nigeria.

It is not my intention here to discuss the substance of Adokiye's allegation. Rather there is something else that caught my attention in the arguments that pit dozens of Nigerians against each other on that discussion forum.

What caught my intention is the number of people who SUPPORTED age-cheating. Don't misunderstand me. I am not saying they agreed that there was age-cheating. In fact they insisted no such thing had happened. That was not what bothered me.

What bothered me is their declaration that even if age-cheating existed, Adokiye should not have said anything about it. They said he was unpatriotic to try to expose it. They questioned his motives, and insisted that if he had bad motives, then we shouldn't listen to his allegation even if it was true. They said life was hard for young men in Nigeria, and so if they had to age-cheat to make it out, we should not pour sand in their garri (a Nigerian phrase that roughly translates as spoiling a good thing for them). They said every team age-cheated, and that we had to age-cheat to keep up with them. And they said (and this was really perplexing) that if you support the SENIOR Eagles team, then you cannot criticize age-cheating at the junior levels because (wait till you hear this) the senior team players were guilty too! Yes, they insisted you must boycott all of Nigerian football if you think we shouldn't age-cheat at the youth levels.

Again, none of this proves we do or did age-cheat.

In fact I want to make clear that I am not saying we do or did (nor am I saying we don't or didn't). You see, that ceased to be important to me, as I watched a raging argument in which a majority of the discussants DEFENDED age-cheating as a concept, regardless of whether we do it or not.

The odd thing is this argument raged in the two weeks before our make-or-break World Cup qualifier away at Kenya, which (along with the result between Tunisia and Mozambique in Maputo) would decide whether we qualified for the 2010 World Cup.

The same people who were gladly defending age-cheating would have attacked, trashed and bashed the Nigerian Football Federation, the manager Amodu Shuaibu, and the Eagles' players if we had not qualified for the World Cup. They would have raged and railed, wondered why bad things always happen to Nigeria, called the country all sorts of horrible names, claimed (with inferiority complexes) that Ghana is so much better at electricity, football, blah, blah, blah.

Now there are many things that contribute toward ending up with a national team that is not dominant, and that has to struggle mightily where others (e.g. Ghana and Cote d'Ivoire in the 2010 qualifiers) sail more smoothly. Indeed, every team, even the good ones, goes through a cycle that resembles the sine and cosine curves -- sometimes you are up, sometimes you are down (Ghana just emerged 3 years ago from an extended period of being down).

Still, the way we manage our football at the grassroots and youth levels are part and parcel of the wider picture of dysfunction in Nigerian football. It is both hypocritical and (more importantly) self-defeating to support that, while complaining that our League, our senior national team, and our current international "stars" are not meeting your lofty expectation. You cannot plant pawpaw and harvest yam. Actually in this case, we are not planting anything at all, but are somehow expecting a bumper harvest, and (worst of all) proceed to complain, whine, bitch and moan when no such bountiful harvest occurs.

Seriously, how can you expect any output at all (even electricity generation) to come out optimal, when the input is consistently suboptimal? If you support the input, fine, that is your right, but don't then join me to complain about the output.

Many of those supporting age-cheating claimed Brazil did the same thing. Mind you, there were other countries they mentioned, but the tendency of comparing ourselves to Brazil in football (the "we produced abundant talent, only matched by Brazil" myth) makes them a very apt example to use to counter those who advocate self-defeating behaviour.

I have watched a documentary film crew go to the grassroots children's football club where Brazilian international Kaka got his start. We all knew what Ronaldinho could do while he was still at Gremio, and were thrilled by Robinho while still at Santos. There is no comparison in Nigeria. It is not just the fact that the histories of "young" players are shrouded in mystery, rumour and innuendo, but the League itself can not be compared to the Brazilian league.

There was a time in life that I stopped taking our age-restricted successes seriously. What little regard I had for them quenched after our success at the age-restricted 1996 Atlanta Olympics. We won that tournament using our de facto national team (minus Finidi), comprising 1994 World Cup and Nations Cup veterans, players from the Under-17 triump in 1993, and a sprinkling of others (notably Victor Ikpeba, from the 1989 Under-17 team).

We beat Brazil (yes, them, I bet you know where this is going) in the semifinals of the 1996 Olympics, in one of the greatest comebacks in our history. That Brazilian team, and those Brazilian players, went on to make it to the final of the 1998 World Cup, went on to WIN the 2002 World Cup, and quite a few of them were still around and kicking when Brazil made it as far as the final eight in 2006.

By contrast, the 1996 Nigerian Olympians, heroes of the nation went on to ..... well, there were a lot of blowout losses in 1998, most significantly to Denmark in 1998, and a general continuation of the 15 years of decline that began in 1994 and continued up till 2008. And it is not yet uhuru (permit me to misuse the term) in 2009, though our qualification for the World Cup could turn out to be the first spark of the revival.

One team in that 1996 semifinal was around the starting point of an upward growth in their developmetnal process, while the other team was at the height of its abilities (remember many of them had won the 1994 Nations Cup).

I will leave it at that. It is not my thesis that we are age-cheats. It is my thesis that we cannot point to Brazil, claim (without proof) that they age-cheat, and then insist that if they do it, we can do it too. Haba, the Brazilians have a football system that produces world champions, world players of the year, and some of the best players in the history of football, on a continuous and consistent basis. To point to them, and say that they are proof that it is okay for us to do the wrong thing, the stupid thing, the self-defeating thing, is insane.

In fact, we shouldn't compare ourselves to ANYBODY, successful or not. The question should be, "Does it work for Nigeria? Does it achieve Nigeria's goals?" If your goal is endlessly winning kiddie tournaments, that is one thing, but if you are looking to be a long-term, permanent, continuous WORLD POWER, then you cannot possibly bring yourself to support the continued absence of the necessary structures and foundations.

But I am (as always) starting to digress.

The point I am making is that for all our complaining about issues, we are often the footsoldiers who fight to protect, defend, sustain and continue the exact things that produce the outcomes we complain about.

In fact, that is why we have "bad leaders". These so-called leaders were born into the same families as the rest of us, into the same lives we all lead, except some quirk of fate gave them a chance to step into leadership. And you know what? The things they do once in office are the same things too many of the rest of us would do if we got that same chance. Far too many of us spend our days hoping and praying for the chance to do exactly what "they" are doing.

But then we complain when the persistence of such decision-making leads to problematic output and negative outcomes.

It is too difficult to try to change all of Nigeria at once. By contrast, we can all change ourselves as individuals, which would have the effect of changing all of Nigeria.

The thing is, it has to be in the context of a revolution, because we all have to do it at the same time. If only one person changes, and everyone else remains the same, then he or she will simply lose out in the vicious competition for survival under the current system. This is the fear that keeps Nigeria from reform, transformation and substantive change -- the fear that if I or you change alone as individuals, no one else will, and the only result would be the loss of our individual niche in the system.

07 November, 2009

What is a "Natural" Country?

Everywhere you go, you hear people say that African countries are unnatural colonial constructs. Many Africans believe this explains many of our post-colonial problems; non-Africans who perceive themselves to be "liberal" or "progressive" say the same thing. [Of course many other non-Africans quietly believe racial theories of intelligence explain Africa's difficultues, though they would never admit it openly in the world of 21st century politically correctness -- some don't even admit it openly to themselves. But that particularly brand of persistent insanity is not the focus of this blog post.]

No, this post focuses on the theory that most every problem in Africa flows from the multi-ethnic, multi-religious, "artificial" borders of post-colonial African federal or unitary republics. They say the borders split contiquous geo-culture zones apart, and forced other geo-culture zones together, that the borders do not follow any rational geographic or geologic sense. That the borders are a causal factor in our post-colonial crises.

Yeah, that theory. It is very popular. I don't think a single person argues against it.

Which is one of the key reasons our different crises take the (false) appearance of being insoluble. It is difficult, oft impossible, to solve a problem if you deceive yourself about what the problem actually is and about what actually causes the problem. You end up deceiving yourself about what will treat the symptoms and stop the causative factors, and investing a lot of energy, effort and resources on roads that do not take you anywhere.

Somalia is a country with only one ethnicity and only one religion, yet it is the most extreme example of post-colonial crisis in Africa. The causal factors behind the persistent Somali crisis (and for the record, it began decades before the events depicted in Black Hawk Down) are the same causal factors behind crises elsewhere in Africa. I could go into detail here (trust me I can), but surely this is enough to let everyone know that it has nothing to do with having many ethnic groups within your borders.

But lets stick with Somalia for a second so I can tell militant atheists and fundamentalist Christians that Islam is not the issue either. The Hutus and Tutsis of Rwanda and Burundi are all predominantly Roman Catholic. Come to think of it, the Hutus and Tutsis also share a single language known as Kinyarwanda in Rwanda and Kirundi in Burundi. Think about that for a second. For all the media and pop culture descriptions of Hutus and Tutsis as irrevocable foes bent on each other's destruction, in fact these are two peoples that share the same language, the same religion, the same black skin, and have lived together in the same geographic space for centuries; are they really "two" peoples are just one? Not surprisingly, the same people who blame colonial borders also blame the Belgians for the Rwanda-Burundi post-colonial crises. I know the Belgians did a lot of physical, economic and psychological damage in Ruanda-Urundi and the Congo, but 34 years after the "Independence" era, we should be looking elsewhere for causality -- or did the Belgians create the "Ivorite" ideology that helped speed the Cote d'Ivoire along to civil war? At the very least we should look squarely at Rwanda and Burundi and ask why the "Belgian problem" (if that is what it is) persisted so long after Independence, or perhaps more properly why there were no social/political/cultural/economic developments to wipe out the supposed "Belgian problem".

So Africa's crises, past and/or present are not a function of multi-ethnicity or religious plurality; the same things happen in mono-culture countries.

You know what? It isn't a Sub-Saharan or Black African thing, either. There has been violence (particularly in Algeria), repression and autocracy in the Maghreb and Egypt. There has also been disputes over language and culture between the Imazighen (once termed "Berbers") and Arabs in those countries. And as much as I criticize and ridicule Nigerian politics, the political situation in Madagascar is so much worse.

I feel I should make something clear at this point, given the fact that any number of non-Africans (and Africans, sadly enough) think there is something wrong with us as a people. Forget the subliminal messages embedded in the international news coverage -- violence and warfare are not unique to Africa. Historically, the wars of the Europeans and the European settlers in the Americas and Australasia, in Europe and outside it, against themselves and near-genocidally against non-European peoples, have wrought more death on Earth than the wars of any other global region. And ditch the myth of Europe learning from World War II and embracing peace; Europe was not at peace, and and the "Cold" War was never actually Cold -- the Europeans and Americans continued fighting each other after 1945, but were careful to do it in other people's countries (the so-called proxy wars), using the rest of the world's cities and villages as their theatres and the rest of the world's bodies as their cannon fodder. More recently, the war of the Serbs, Croats and Bosnians was not too dissimilar from those of the Rwandans and Burundians (peoples who speak the same language, in their case Serbo-Croatian) or from the recurrent violence in Nigeria (pitting people who are basically the same against each other based on which external religious proselytizers reached which regions first).

But this is another digression. This blog post is not about humanity's addiction to strife, dischord and violence. It is instead about the assertion that African countries are "artificial", and that this artificiality is the source of much of our post-colonial angst.

Here is a newsflash for you: Every country in the world is artificial, and every ethno-cultural group is artificial too. All of them were created, directly or indirectly, by war -- just like the modern borders of post-colonial Africa.

Every boundary on the global map was created by vicious, bloody war. No nation just miraculously came to be. Every one of them was created by armies, empire-builders, would-be monarchs, warlords, slave-raiders, colonizers, occupiers, genocidaires and others skilled at warfare and killing. The nations of the Americas, North and South, are all "artificial creations". Seemingly "natural" island-nations, like Japan and Britain, were created from pre-existing smaller entities that were merged forcibly through war.

The massive landmass of Eurasia has seen the ebb and flow of uncountable "national" boundaries over thousands of years, with a prodigious number of changes taking place over the last 110 years alone. War was the source, peace the confirmation, of all of these borders and boundaries. Part of Russia used to be Finland; all of Taiwan used to be (how do I put this?) governed from Beijing. "Saudi Arabia" came into being not too long before Nigeria's Amalgamation. And while there were always Kazakhs in Central Asia, there was no "Kazakhstan" until the Cold War (there is that word again, "war") came to an end -- leading to the dismantling of a Russian Empire that was itself created in war.

The idea that Africa's problems arise from "unnatural" borders ignores the fact that all of the world's richest nations have borders that are just as "unnatural" as ours. What is "natural" about the United States or Canada? Is there something "natural" about the Korean peninsula (home to South Korea) being divided in two?

When some Africans look at France (for example), they see everyone in the country speaks French, and they conclude that a reason for French success (and African difficulty) is the "natural" effect of a single culture living in the boundaries of a nation-state.

This is laughable.

Firstly, France is itself a product of external colonialism and empire-building.

Secondly, the "single culture" of France was imposed on peoples who were initially as diverse as the peoples within post-colonial African borders. The "French people" descend from Scandinavian Norsemen, Celtic peoples, Germanic people, Latin people and even Central Asian peoples. If you see them speaking French today, know they do it for the same reason "Francophone" countries in Africa do -- a central government and/or economic system that directly or indirectly forces a single language onto people who used to speak other tongues. And even after condition made the crayfish bend (as we say in Nigeria), with French emergent as the dominant language in the area, as recently as the era of Jeanne d'Arc, the modern-day French region of Burgundy de facto insisted upon its independence and separation from France, with an eye on recovering the sprawling empire controlled by previous generations of Burgundians in a prior age when "France" was considered an unnatural idea. Oddly enough, it was the Jeanne-d'Arc-assisted victory of the French over the English in the 100 Years Wars (there it is again, "war") that confirmed the existence of "France" as we know it today. Had they lost, a large portion of today's France would either have been a mainland Europe equivalent of Northern Ireland, a mainland equivalent of the Republic of Ireland, or an English-speaking cross-channel variant of the Austria-Germany dynamic.

That everyone in France speaks French today is about as "natural" as everyone in tdoay's Nigeria speaking English and Pidgin English. Our ancestors did not speak English. What happened between then and now was the British military invasion, and the after-effects of that invasion. Provided the effects of the wars last long enough, the passage of time (and the centralization of commerce and government) tends to produce a homogenization of previously disparate peoples, a convergence to a new socio-political norm.

This tendency towards covergence is how every modern ethnicity came to be. The vast "Arab" peoples of today are descended from a variety of peoples, ranging from Phoenicians and other Aramaics to Greeks, Turkic, South Asians and Black Africans. The sprawling Kanuri peoples of Nigeria are also the result of homogenizing changes brought to conquered peoples by the over-a-millennia-old empire of Borno-Kanem.

Which bring up an important point. At least it is important to me. You see, one of the things I most love about Nigeria is its rich, incredible cultural, linguistic and religious diversity. However, if "Nigeria" lasts long enough, the same thing that happened to "France" or "United States of America" or even "China" will happen here too -- a drift towards homogenization and convergence. One could argue that underneath a surface of visible internecine strife, said convergence has already been occuring; and perhaps a lot of the reflexive traits when term "tribalism" derive from a fear of this convergence, a fear that it means "we" will lose "our" culture as it gets swamped by "their" culture (or by Euro-American "Western" values, or by Saudi Arabian values).

The ideal, transformative constitution for Nigeria must be constructed such that our geo-cultural groups are the building blocks; provided there is a Tiv province or district, for example, there will be a Tiv social, political, cultural,educational and economic construct. The new federal republc we create must be built on these pillars of our traditions, languages and cultures; the act of governance itself must reinforce our diversity. Accomplishing this without strangling our unity is not as hard as it appear -- and is a topic for discussion another day.

The point is, all countries are artificial creations. Even if you revise Africa's boundaries to make them all single-ethnicity republics, the new republics will be artificial too, as they would correspond to NO historic kingdom, empire or political unit in African history. The idea that doing so would constitue restoring the precolonial past is fallacious. There was no Republic of Hausa or Republic of Igbo in the past; the city-states of Hausaland and the Igbo village republics were independent entities. A similar truth held for other peoples, like the Ijaw and Tiv. The only constant in our history was change, with the Yoruba and Jukun, for example, going through different political iterations over the centuries. Which one of these is the "authentic" one we are supposed to restore? Why should we assume that "Republic of Yoruba" would not be prone to the same divisionist and irredentist pressures as the Federal Republic of Nigeria? After all, the Oyo Empire split apart at the end of the 19th Century pretty much the same way the Russian Empire did at the end of the 20th.

And why are we obsessing over these borders, when the crucial, critical issues (the issues that made Somalia what it is today, the issues that hobble Nigeria's march to its potential) continue to be ignored? I mean, who gives a rat's nyash about the borders?

Yes, the borders cut through "natural" geographic and economic zones. But you know what? We can TRADE across those borders so freely that it doesn't matter that a border is there.

Yes, the borders cut across "natural" ethno-cultural groups. Again, you know what? With free movement across the borders, peoples with shared traditions can practice those traditions together, even if a "border" putatively exists across their lands.

Nothing stops nomadic herdsmen from moving between Nigeria, Chad and the Niger Republic, interacting with peoples and environments the way they always have. The same could apply to other social, cultural and economic groups.

At the end of the day, the borders are not as important as they are made out to be. In fact, any "barriers" as exist are created by us, by human beings, by our governments and by governmental policy. That is what is not natural.

It is not natural for our governments to behave as if the borders are the Great Wall of China. It is not natural for our governments to make economic policy as if they were islands disconnected from their neighbours.

In fact, our post-colonial governments have continued the colonial-era practice of making policy as if the most important relationship is that between us (the colonized) and the Euro-American "West". Where this colonial bond has weakened, it was replaced by new colonial bonds to the erstwhile Soviet Union or to the 21st century Peoples Republic of China. Saudi Arabia may lack political clout on the continent, but its cultural influence is strong in particular regions.

We have politicians, businessmen, and (to be honest) citizens as well, who downgrade intra-African relationships, and then blame inanimate political borders for the lines that separate us.

I am sorry, but I am sick and tired of hearing about "Pan-Africanism", "Black Unity", "NEPAD", "United States of Africa" and all the rest of the malarkey. These empty phrases and ideologies have become crutches. Instead of doing the practical and substantive things that build intra-African development, we invest our time repeating the same tired phrases that have never translated into anything practical.

You know what? If Rwanda (currently led by Paul Kagame) and Burundi (currently led by Pierre Nkurunziza) were serious about "integration" and "unity", their two countries would long since have merged to become one. But this has not happened. They very deliberately sidestep this, in favour of blandishments about East African Unity and a "Union Government" of Africa -- two "unnatural" concepts favoured over that most natural of unions joining the Kinyarwanda/Kirundi peoples (they can't even give their shared language a single name). Seriously, if two people who are exactly the same cannot come to the decision to share a government, what makes anyone think they will manage it long-term in a much broader, much less "natural" setting?

Now I am digressing AND rambling.

Actually, no I am not.

The "East African Federation" project is exactly the sort of thing I am talking about. If I made a list of the things holding Kenya back, a list of the thing hobbling Uganda, and a list of priorities for Tanzania, the creation of new supra-national borders will not make any of the lists.

There is a lot of talk in East Africa about the larger market, and how it will solve all of their problems. The thing is, Nigeria is a larger market (alone we are as populated as all of East Africa), so they should trust me when I say their problems will still be waiting for them after they create this larger market.

We have got to face the core problems, and stop playing around with borders or using them as an excuse or crutch. You might have noticed I did not actually make lists of the core issues Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania or Rwanda/Burundi need to address, because such a list would turn this blog post into a multi-volume set of thick e-books. And the lists (items, analyses, prescriptions and recommendations) are that long precisely because they continue to pile up, decade after decade, while we obsess about borders and "artificiality".

Put down the crutch and WALK. We might then discover that there was nothing wrong with our legs all along. Heck, we might even begin to RUN to development, instead of shuffling along slowly, telling ourselves that our legs are "artificial".

No, this post focuses on the theory that most every problem in Africa flows from the multi-ethnic, multi-religious, "artificial" borders of post-colonial African federal or unitary republics. They say the borders split contiquous geo-culture zones apart, and forced other geo-culture zones together, that the borders do not follow any rational geographic or geologic sense. That the borders are a causal factor in our post-colonial crises.

Yeah, that theory. It is very popular. I don't think a single person argues against it.

Which is one of the key reasons our different crises take the (false) appearance of being insoluble. It is difficult, oft impossible, to solve a problem if you deceive yourself about what the problem actually is and about what actually causes the problem. You end up deceiving yourself about what will treat the symptoms and stop the causative factors, and investing a lot of energy, effort and resources on roads that do not take you anywhere.

Somalia is a country with only one ethnicity and only one religion, yet it is the most extreme example of post-colonial crisis in Africa. The causal factors behind the persistent Somali crisis (and for the record, it began decades before the events depicted in Black Hawk Down) are the same causal factors behind crises elsewhere in Africa. I could go into detail here (trust me I can), but surely this is enough to let everyone know that it has nothing to do with having many ethnic groups within your borders.

But lets stick with Somalia for a second so I can tell militant atheists and fundamentalist Christians that Islam is not the issue either. The Hutus and Tutsis of Rwanda and Burundi are all predominantly Roman Catholic. Come to think of it, the Hutus and Tutsis also share a single language known as Kinyarwanda in Rwanda and Kirundi in Burundi. Think about that for a second. For all the media and pop culture descriptions of Hutus and Tutsis as irrevocable foes bent on each other's destruction, in fact these are two peoples that share the same language, the same religion, the same black skin, and have lived together in the same geographic space for centuries; are they really "two" peoples are just one? Not surprisingly, the same people who blame colonial borders also blame the Belgians for the Rwanda-Burundi post-colonial crises. I know the Belgians did a lot of physical, economic and psychological damage in Ruanda-Urundi and the Congo, but 34 years after the "Independence" era, we should be looking elsewhere for causality -- or did the Belgians create the "Ivorite" ideology that helped speed the Cote d'Ivoire along to civil war? At the very least we should look squarely at Rwanda and Burundi and ask why the "Belgian problem" (if that is what it is) persisted so long after Independence, or perhaps more properly why there were no social/political/cultural/economic developments to wipe out the supposed "Belgian problem".

So Africa's crises, past and/or present are not a function of multi-ethnicity or religious plurality; the same things happen in mono-culture countries.

You know what? It isn't a Sub-Saharan or Black African thing, either. There has been violence (particularly in Algeria), repression and autocracy in the Maghreb and Egypt. There has also been disputes over language and culture between the Imazighen (once termed "Berbers") and Arabs in those countries. And as much as I criticize and ridicule Nigerian politics, the political situation in Madagascar is so much worse.

I feel I should make something clear at this point, given the fact that any number of non-Africans (and Africans, sadly enough) think there is something wrong with us as a people. Forget the subliminal messages embedded in the international news coverage -- violence and warfare are not unique to Africa. Historically, the wars of the Europeans and the European settlers in the Americas and Australasia, in Europe and outside it, against themselves and near-genocidally against non-European peoples, have wrought more death on Earth than the wars of any other global region. And ditch the myth of Europe learning from World War II and embracing peace; Europe was not at peace, and and the "Cold" War was never actually Cold -- the Europeans and Americans continued fighting each other after 1945, but were careful to do it in other people's countries (the so-called proxy wars), using the rest of the world's cities and villages as their theatres and the rest of the world's bodies as their cannon fodder. More recently, the war of the Serbs, Croats and Bosnians was not too dissimilar from those of the Rwandans and Burundians (peoples who speak the same language, in their case Serbo-Croatian) or from the recurrent violence in Nigeria (pitting people who are basically the same against each other based on which external religious proselytizers reached which regions first).

But this is another digression. This blog post is not about humanity's addiction to strife, dischord and violence. It is instead about the assertion that African countries are "artificial", and that this artificiality is the source of much of our post-colonial angst.

Here is a newsflash for you: Every country in the world is artificial, and every ethno-cultural group is artificial too. All of them were created, directly or indirectly, by war -- just like the modern borders of post-colonial Africa.

Every boundary on the global map was created by vicious, bloody war. No nation just miraculously came to be. Every one of them was created by armies, empire-builders, would-be monarchs, warlords, slave-raiders, colonizers, occupiers, genocidaires and others skilled at warfare and killing. The nations of the Americas, North and South, are all "artificial creations". Seemingly "natural" island-nations, like Japan and Britain, were created from pre-existing smaller entities that were merged forcibly through war.

The massive landmass of Eurasia has seen the ebb and flow of uncountable "national" boundaries over thousands of years, with a prodigious number of changes taking place over the last 110 years alone. War was the source, peace the confirmation, of all of these borders and boundaries. Part of Russia used to be Finland; all of Taiwan used to be (how do I put this?) governed from Beijing. "Saudi Arabia" came into being not too long before Nigeria's Amalgamation. And while there were always Kazakhs in Central Asia, there was no "Kazakhstan" until the Cold War (there is that word again, "war") came to an end -- leading to the dismantling of a Russian Empire that was itself created in war.

The idea that Africa's problems arise from "unnatural" borders ignores the fact that all of the world's richest nations have borders that are just as "unnatural" as ours. What is "natural" about the United States or Canada? Is there something "natural" about the Korean peninsula (home to South Korea) being divided in two?

When some Africans look at France (for example), they see everyone in the country speaks French, and they conclude that a reason for French success (and African difficulty) is the "natural" effect of a single culture living in the boundaries of a nation-state.

This is laughable.

Firstly, France is itself a product of external colonialism and empire-building.

Secondly, the "single culture" of France was imposed on peoples who were initially as diverse as the peoples within post-colonial African borders. The "French people" descend from Scandinavian Norsemen, Celtic peoples, Germanic people, Latin people and even Central Asian peoples. If you see them speaking French today, know they do it for the same reason "Francophone" countries in Africa do -- a central government and/or economic system that directly or indirectly forces a single language onto people who used to speak other tongues. And even after condition made the crayfish bend (as we say in Nigeria), with French emergent as the dominant language in the area, as recently as the era of Jeanne d'Arc, the modern-day French region of Burgundy de facto insisted upon its independence and separation from France, with an eye on recovering the sprawling empire controlled by previous generations of Burgundians in a prior age when "France" was considered an unnatural idea. Oddly enough, it was the Jeanne-d'Arc-assisted victory of the French over the English in the 100 Years Wars (there it is again, "war") that confirmed the existence of "France" as we know it today. Had they lost, a large portion of today's France would either have been a mainland Europe equivalent of Northern Ireland, a mainland equivalent of the Republic of Ireland, or an English-speaking cross-channel variant of the Austria-Germany dynamic.

That everyone in France speaks French today is about as "natural" as everyone in tdoay's Nigeria speaking English and Pidgin English. Our ancestors did not speak English. What happened between then and now was the British military invasion, and the after-effects of that invasion. Provided the effects of the wars last long enough, the passage of time (and the centralization of commerce and government) tends to produce a homogenization of previously disparate peoples, a convergence to a new socio-political norm.

This tendency towards covergence is how every modern ethnicity came to be. The vast "Arab" peoples of today are descended from a variety of peoples, ranging from Phoenicians and other Aramaics to Greeks, Turkic, South Asians and Black Africans. The sprawling Kanuri peoples of Nigeria are also the result of homogenizing changes brought to conquered peoples by the over-a-millennia-old empire of Borno-Kanem.

Which bring up an important point. At least it is important to me. You see, one of the things I most love about Nigeria is its rich, incredible cultural, linguistic and religious diversity. However, if "Nigeria" lasts long enough, the same thing that happened to "France" or "United States of America" or even "China" will happen here too -- a drift towards homogenization and convergence. One could argue that underneath a surface of visible internecine strife, said convergence has already been occuring; and perhaps a lot of the reflexive traits when term "tribalism" derive from a fear of this convergence, a fear that it means "we" will lose "our" culture as it gets swamped by "their" culture (or by Euro-American "Western" values, or by Saudi Arabian values).

The ideal, transformative constitution for Nigeria must be constructed such that our geo-cultural groups are the building blocks; provided there is a Tiv province or district, for example, there will be a Tiv social, political, cultural,educational and economic construct. The new federal republc we create must be built on these pillars of our traditions, languages and cultures; the act of governance itself must reinforce our diversity. Accomplishing this without strangling our unity is not as hard as it appear -- and is a topic for discussion another day.

The point is, all countries are artificial creations. Even if you revise Africa's boundaries to make them all single-ethnicity republics, the new republics will be artificial too, as they would correspond to NO historic kingdom, empire or political unit in African history. The idea that doing so would constitue restoring the precolonial past is fallacious. There was no Republic of Hausa or Republic of Igbo in the past; the city-states of Hausaland and the Igbo village republics were independent entities. A similar truth held for other peoples, like the Ijaw and Tiv. The only constant in our history was change, with the Yoruba and Jukun, for example, going through different political iterations over the centuries. Which one of these is the "authentic" one we are supposed to restore? Why should we assume that "Republic of Yoruba" would not be prone to the same divisionist and irredentist pressures as the Federal Republic of Nigeria? After all, the Oyo Empire split apart at the end of the 19th Century pretty much the same way the Russian Empire did at the end of the 20th.

And why are we obsessing over these borders, when the crucial, critical issues (the issues that made Somalia what it is today, the issues that hobble Nigeria's march to its potential) continue to be ignored? I mean, who gives a rat's nyash about the borders?

Yes, the borders cut through "natural" geographic and economic zones. But you know what? We can TRADE across those borders so freely that it doesn't matter that a border is there.

Yes, the borders cut across "natural" ethno-cultural groups. Again, you know what? With free movement across the borders, peoples with shared traditions can practice those traditions together, even if a "border" putatively exists across their lands.

Nothing stops nomadic herdsmen from moving between Nigeria, Chad and the Niger Republic, interacting with peoples and environments the way they always have. The same could apply to other social, cultural and economic groups.

At the end of the day, the borders are not as important as they are made out to be. In fact, any "barriers" as exist are created by us, by human beings, by our governments and by governmental policy. That is what is not natural.

It is not natural for our governments to behave as if the borders are the Great Wall of China. It is not natural for our governments to make economic policy as if they were islands disconnected from their neighbours.

In fact, our post-colonial governments have continued the colonial-era practice of making policy as if the most important relationship is that between us (the colonized) and the Euro-American "West". Where this colonial bond has weakened, it was replaced by new colonial bonds to the erstwhile Soviet Union or to the 21st century Peoples Republic of China. Saudi Arabia may lack political clout on the continent, but its cultural influence is strong in particular regions.

We have politicians, businessmen, and (to be honest) citizens as well, who downgrade intra-African relationships, and then blame inanimate political borders for the lines that separate us.

I am sorry, but I am sick and tired of hearing about "Pan-Africanism", "Black Unity", "NEPAD", "United States of Africa" and all the rest of the malarkey. These empty phrases and ideologies have become crutches. Instead of doing the practical and substantive things that build intra-African development, we invest our time repeating the same tired phrases that have never translated into anything practical.

You know what? If Rwanda (currently led by Paul Kagame) and Burundi (currently led by Pierre Nkurunziza) were serious about "integration" and "unity", their two countries would long since have merged to become one. But this has not happened. They very deliberately sidestep this, in favour of blandishments about East African Unity and a "Union Government" of Africa -- two "unnatural" concepts favoured over that most natural of unions joining the Kinyarwanda/Kirundi peoples (they can't even give their shared language a single name). Seriously, if two people who are exactly the same cannot come to the decision to share a government, what makes anyone think they will manage it long-term in a much broader, much less "natural" setting?

Now I am digressing AND rambling.

Actually, no I am not.

The "East African Federation" project is exactly the sort of thing I am talking about. If I made a list of the things holding Kenya back, a list of the thing hobbling Uganda, and a list of priorities for Tanzania, the creation of new supra-national borders will not make any of the lists.

There is a lot of talk in East Africa about the larger market, and how it will solve all of their problems. The thing is, Nigeria is a larger market (alone we are as populated as all of East Africa), so they should trust me when I say their problems will still be waiting for them after they create this larger market.

We have got to face the core problems, and stop playing around with borders or using them as an excuse or crutch. You might have noticed I did not actually make lists of the core issues Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania or Rwanda/Burundi need to address, because such a list would turn this blog post into a multi-volume set of thick e-books. And the lists (items, analyses, prescriptions and recommendations) are that long precisely because they continue to pile up, decade after decade, while we obsess about borders and "artificiality".

Put down the crutch and WALK. We might then discover that there was nothing wrong with our legs all along. Heck, we might even begin to RUN to development, instead of shuffling along slowly, telling ourselves that our legs are "artificial".

02 November, 2009

Stereotypes, Prejudices and Violence

I rarely go to the cinema, and when I do, I never go on opening weekend. If you wait a while, you can enjoy the same film on the giant screen in less-crowded circumstances. There have been zero movies I thought were so good that I had to go see them early, lest they prove commercial failures and disappear from theatres before I can see them. Like I said, I rarely go to the cinema anyway (and no, I don't watch much TV either).

Yet there I sat, in a stuffily crowded theatre to see District 9. In the ads, it looked like something I'd enjoy. More importantly, it was a big-budget, sci-fi action movie shot in Africa (South Africa) with a mostly African cast and an African writer/director; big box office numbers on the opening weekend (assisted by my $10.00 ticket) could mean more of the same in the future. The beneficiaries of such future investment would likely be South Africa, Botswana and the other handful of countries that combine the "safari-style" locations the rest of world believes to be "Africa", and a global reputation for being "stable" in the African context. South Africa has the additional benefits of urban landscapes familiar to Europe/America (I know of one film, starring the beautiful Rachel True, that was set in Southern California, but which was actually filmed in Sandton City, north of Johannesburg).

I don't care that Nigeria would not be a direct beneficiary; the continent of Africa needs economic expansion and job-creation desperately. Even South Africa is facing problems with high unemployment and under-employment. Besides, Nigeria has its own film industries (plural, because of the different independent nodes). I hope and pray Nigeria's film industries raise the quantity of investment, as well as the quality of output, so we can tap into global markets as the "voice" of African movie-making. This is already happening; compare recent output with output from the early days and you can see a clear upward trajectory on all counts. Long may it continue.

Yeah, I felt great sitting there, supporting the "African" film industry, watching District 9 amidst the close-packed crowd, as the movie began. Alas, midway through the film, I deeply regretted wasting my hard-earned money on yet another example of South African Naijaphobia.

District 9 is supposed to be an allegorical film; everything is a metaphor or stand-in for something else. Allegories are not meant to be blunt instruments. That staple of fiction, the archetype, is the preferred tool of this most distinguished of genres. The reader (or in this case viewer) either instantly knows or discovers along the way that the name and circumstances of the archetype are irrelevant; it is what he, she or it represents that is important. Animal Farm by George Orwell is one of the best in the genre; read it if you haven't already.

In District 9, the extra-terrestrial Prawns symbolized refugees, illegal aliens, foreigners targeted for xenophobia and black South Africans under Apartheid. Multinational United (hence MNU), stood in for powerful, globe-spanning businesses, but also governments, governmental bureaucracies and civil services, and (I suspect) for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as well. And the worst crimes and catastrophes in history were possible only because of seemingly decent, "just doing my job and making a living" people like the character Wikus Van Der Merwe -- they act without malice or malevolence, in line with the operative societal ethos (if it is wrong, it would be illegal, they say to themselves) but without them, no big, eye-catching horror would have been possible.

The South African writer/director of District 9 set his tale in "Johannesburg" but beyond that, nothing in the story is connected to the real world, and everything is a metaphor disconnected from any real person or entity. If there was a South African government in the world of District 9, it was a curiously invisible body that allowed MNU act as thought it were the government. Indeed, the writer/director was careful to make clear Multinational United's mandate came from some fictional, metaphoric stand-in for the United Nations (itself probably an allegoric comment on the UN's policies and performance in such situations).

Everything was a metaphor, symbolic, a stand-in. Everything except the disgusting, ultra-violent, sub-human criminals who exploited the Prawns. These were clearly identified as "Nigerians".

In an allegorical context, you need only depict the criminal archetype. If there was a need to ascribe a name to them, it could have been something blandly decriptive, in the way "Multinational United" is a very unimaginative name for a "multinational" business. He could have said "gangs" and everyone in the world would understand what you meant. He could have said "organized crime" and everyone would know what he meant. We all watched the mercenaries hired by MNU, and we all knew exactly what and who they represented, but we did not care about the nationality and citizenship of the mercenaries, did we? Were they Ukrainian? French? Russian? South African? Who cared? They were "mercenaries", hired killers, and we understood.

So why did the retch-inducing crimninals have to be "Nigerians"?

Because in South Africa, "Nigerian" is the archetype for "dreadful criminal". In much the same way as we all understood the other archetypes, the South African writer/director of District 9 expected us to understand the moment we heard the word "Nigerian". In truth, we Nigerians are the victims of dreadful stereotyping worldwide, so I guess he figured the whole world would understand the metaphor; the people exploiting the vulnerable and broken Prawns represented the worst of humanity, ipso facto "Nigerians".

Had he not ascribed a specific nationality to the crooks, the viewers might have assumed they were "South African" like everyone else in the movie, except we all knew as viewers that these "South African" characters were not in fact South African at all, but were commentaries on all of us; indeed, all of our nations have nasty, disgusting criminals. But no, the bloody man had to specify, just so we know, that these were "Nigerians".

Mind you, this blog post is NOT about countering the world's stereotypes about Nigerians. True, we seem to be the only people in the world for whom it is still politically correct to hold and express nasty stereotypical views. So what if the Nigerians narcotics industry is microscopic compared to its peers in the United States, the EU-members, Latin America and South and Southeast Asia? So what if every Naira and Dollar stolen by 419 operators combined is nothing compared to the individual frauds of Madoff, Enron, and quite frankly the entire global financial industry (which seems to have been either a giant Ponzi scheme professing to have created wealth where none existed, or a 419 scheme inspiring millions to exchange real money for make-believe value). I cannot think of a single criminal endeavor in which Nigerians are the world's number one, yet we get typecast as genetic crooks or something.

No, this is not about that.

This is about my fellow Nigerians, participants in a discussion form I am part of. You see, in the aftermath of District 9, a thread was started to discuss the extremely negative perception of Nigerians in South African pop culture. As this South African writer laments in the Mail and Guardian ( paragraph 13 ), "Must Nigerians always be the bad guys?" Ironically, the Mail and Guardian is one of a handful of South African news sources that have angered me over the years with reporters and columnists just casually repeating what are nasty stereotypes about Nigerians as if they were confirmed facts.

The thing that flabbergasted me, that always flabbergasts me when topics like this come up, is the NIGERIAN discussants on the forum in question predominantly agreed (over 85% by rough estimate) that we Nigerian had EARNED the negative reputation South Africans had of us. As always, the existence of Nigerian criminals in the "other" country (doesn't matter what country) as proof that Nigerians were deservedly identified as criminals.

Again, this blog post is not intended to argue against this obviously wrong, and obviously stupid conclusion. I wouldn't waste my time on that.

There is something more important here.

Black Africans and people of Black African descent worldwide have a hair-trigger, knee-jerk reaction to "racism" from every other "race". It doesn't take much for a non-black person to be accused of racism by a black person.

While we spend all our energy chasing "external racism", we seem oblivious to the fact that the biggest threat to Black Africans is the racism of Black Africans against other Black Africans.

Our nasty stereotypes about each other, prejudice toward each other, our superiority complexes focused on each other, distrust of each other, internal discrimination and segregation from each other, and in extreme cases our hatred of each other are prime causative factors of our stagnation, the slow pace of our progress, and of the disasters (including violent, murderous massacres) that scar our continent. It is why our countries are weak; and frankly, given the fact that such behaviour exists even between sub-groups of the same ethnicity and/or religion, the idea that the blame lies with "colonial" borders creating multi-ethnic countries is farcical. If we do not defeat black-on-black prejudice, it will continue to bite us in the nyash whether we break the colonial lines or not.

It baffles me that any Nigerians would suggest that any manifestation of this black-on-black prejudice was justifiable. If Nigerians are so terrible that South Africans are justified in holding prejudices against us, how does that explain the prejudice and recurrent VIOLENCE in South Africa against Mozambicans, Somalians, Malians and Zimbabweans? Are they genetic criminals too?

If it seems I am scapegoating South Africa, trust me, I am not.

This black-on-black prejudice and VIOLENCE exists in Nigeria too. In Rwanda. In Burundi. In Senegal. In Cote d'Ivoire. In both Congos. In Kenya. In Zimbabwe; it is strange that the world reacted when Mugabe turned on the white farmers, but no one, sadly not even African countries, said anything during or after the Mugabe regime's black-on-black, Shona-vs-Ndebele Gukurahundi massacres of the early 1980s. In (amazingly and depressingly) uni-lingual, uni-religious, uni-cultural Somalia.

I could go on and on and on, but the point is simple. The exterior descriptions of the prejudices differ from place to place (though the belief that "they" are trying to politically and economically dominate "us" is the most popular), with the same single person or group of people often holding different negative prejudices for different peoples in their vicinity. The "explanations" and "rationales" people offer themselves and others for their prejudicial beliefs are different (a Gambian I know excused violence against Somali refugees in another African country because, as he put it, "The Somalis are too clannish"; yes, that was his explanation of the murder of human beings and the burning down of their businesses), though the idea that "we" must defend ourselves against "them" is again the most popular.

Substantively the prejudices are based on outright falsehoods, massive exaggerations of comparatively infinitesimal historical facts, wilful and involuntary ignorance, and (above all) the principle of collective punishment where the crimes of a single individual or a small group of individuals serves to indict and convict every other person that shares an ethnicity, religion, region or nationality with the guilty party.

Violence is the consequence of these attitudes, but is treated by true believers as the proof of the belief. As such it becomes a self-reinforcing cycle; it happens because we believe it, and we believe it because it happens.

The sad irony is the South African writer/director of District 9 intended his film to highlight several things about human beings, one of which is our treatment of immigrants within our midst. Yet, by using the South African vision of the criminal archetype, the "Nigerian", he in fact commits the same fault he ostensibly is trying to highlight.

To be honest, by the end of the movie, as I trudged out, angry that I had wasted my money boosting District 9's box office, and entirely aware that I was probably the only person in the cinema who knew (or cared) about South African stereotypes of Nigerians (wouldn't it have been different if the examples of the worst in humanity had been called "Americans" or "Frenchmen" or "Indonesians"), a thought occurred to me: District 9 would have been so much more effective at making its allegorical point if the extra-terrestrial aliens had been called amakwerekwere instead of Prawns. Better yet, he could have called the disgusting, criminals amakwerekwere. Then again, the "Nigerians" and the Prawns had sex, well not so much sex as inter-species prostitution. That does make sense; in real-life South Africa, everyone "knows" the immigrants are responsible for all of the crime; as such, both the Prawns and the "Nigerians" are amakwerekwere, explaining why their sexual organs were compatible enough for inter-species sex.

I wish I could ask for my money back.

Yet there I sat, in a stuffily crowded theatre to see District 9. In the ads, it looked like something I'd enjoy. More importantly, it was a big-budget, sci-fi action movie shot in Africa (South Africa) with a mostly African cast and an African writer/director; big box office numbers on the opening weekend (assisted by my $10.00 ticket) could mean more of the same in the future. The beneficiaries of such future investment would likely be South Africa, Botswana and the other handful of countries that combine the "safari-style" locations the rest of world believes to be "Africa", and a global reputation for being "stable" in the African context. South Africa has the additional benefits of urban landscapes familiar to Europe/America (I know of one film, starring the beautiful Rachel True, that was set in Southern California, but which was actually filmed in Sandton City, north of Johannesburg).

I don't care that Nigeria would not be a direct beneficiary; the continent of Africa needs economic expansion and job-creation desperately. Even South Africa is facing problems with high unemployment and under-employment. Besides, Nigeria has its own film industries (plural, because of the different independent nodes). I hope and pray Nigeria's film industries raise the quantity of investment, as well as the quality of output, so we can tap into global markets as the "voice" of African movie-making. This is already happening; compare recent output with output from the early days and you can see a clear upward trajectory on all counts. Long may it continue.

Yeah, I felt great sitting there, supporting the "African" film industry, watching District 9 amidst the close-packed crowd, as the movie began. Alas, midway through the film, I deeply regretted wasting my hard-earned money on yet another example of South African Naijaphobia.

District 9 is supposed to be an allegorical film; everything is a metaphor or stand-in for something else. Allegories are not meant to be blunt instruments. That staple of fiction, the archetype, is the preferred tool of this most distinguished of genres. The reader (or in this case viewer) either instantly knows or discovers along the way that the name and circumstances of the archetype are irrelevant; it is what he, she or it represents that is important. Animal Farm by George Orwell is one of the best in the genre; read it if you haven't already.

In District 9, the extra-terrestrial Prawns symbolized refugees, illegal aliens, foreigners targeted for xenophobia and black South Africans under Apartheid. Multinational United (hence MNU), stood in for powerful, globe-spanning businesses, but also governments, governmental bureaucracies and civil services, and (I suspect) for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as well. And the worst crimes and catastrophes in history were possible only because of seemingly decent, "just doing my job and making a living" people like the character Wikus Van Der Merwe -- they act without malice or malevolence, in line with the operative societal ethos (if it is wrong, it would be illegal, they say to themselves) but without them, no big, eye-catching horror would have been possible.

The South African writer/director of District 9 set his tale in "Johannesburg" but beyond that, nothing in the story is connected to the real world, and everything is a metaphor disconnected from any real person or entity. If there was a South African government in the world of District 9, it was a curiously invisible body that allowed MNU act as thought it were the government. Indeed, the writer/director was careful to make clear Multinational United's mandate came from some fictional, metaphoric stand-in for the United Nations (itself probably an allegoric comment on the UN's policies and performance in such situations).

Everything was a metaphor, symbolic, a stand-in. Everything except the disgusting, ultra-violent, sub-human criminals who exploited the Prawns. These were clearly identified as "Nigerians".

In an allegorical context, you need only depict the criminal archetype. If there was a need to ascribe a name to them, it could have been something blandly decriptive, in the way "Multinational United" is a very unimaginative name for a "multinational" business. He could have said "gangs" and everyone in the world would understand what you meant. He could have said "organized crime" and everyone would know what he meant. We all watched the mercenaries hired by MNU, and we all knew exactly what and who they represented, but we did not care about the nationality and citizenship of the mercenaries, did we? Were they Ukrainian? French? Russian? South African? Who cared? They were "mercenaries", hired killers, and we understood.

So why did the retch-inducing crimninals have to be "Nigerians"?

Because in South Africa, "Nigerian" is the archetype for "dreadful criminal". In much the same way as we all understood the other archetypes, the South African writer/director of District 9 expected us to understand the moment we heard the word "Nigerian". In truth, we Nigerians are the victims of dreadful stereotyping worldwide, so I guess he figured the whole world would understand the metaphor; the people exploiting the vulnerable and broken Prawns represented the worst of humanity, ipso facto "Nigerians".

Had he not ascribed a specific nationality to the crooks, the viewers might have assumed they were "South African" like everyone else in the movie, except we all knew as viewers that these "South African" characters were not in fact South African at all, but were commentaries on all of us; indeed, all of our nations have nasty, disgusting criminals. But no, the bloody man had to specify, just so we know, that these were "Nigerians".

Mind you, this blog post is NOT about countering the world's stereotypes about Nigerians. True, we seem to be the only people in the world for whom it is still politically correct to hold and express nasty stereotypical views. So what if the Nigerians narcotics industry is microscopic compared to its peers in the United States, the EU-members, Latin America and South and Southeast Asia? So what if every Naira and Dollar stolen by 419 operators combined is nothing compared to the individual frauds of Madoff, Enron, and quite frankly the entire global financial industry (which seems to have been either a giant Ponzi scheme professing to have created wealth where none existed, or a 419 scheme inspiring millions to exchange real money for make-believe value). I cannot think of a single criminal endeavor in which Nigerians are the world's number one, yet we get typecast as genetic crooks or something.

No, this is not about that.

This is about my fellow Nigerians, participants in a discussion form I am part of. You see, in the aftermath of District 9, a thread was started to discuss the extremely negative perception of Nigerians in South African pop culture. As this South African writer laments in the Mail and Guardian ( paragraph 13 ), "Must Nigerians always be the bad guys?" Ironically, the Mail and Guardian is one of a handful of South African news sources that have angered me over the years with reporters and columnists just casually repeating what are nasty stereotypes about Nigerians as if they were confirmed facts.

The thing that flabbergasted me, that always flabbergasts me when topics like this come up, is the NIGERIAN discussants on the forum in question predominantly agreed (over 85% by rough estimate) that we Nigerian had EARNED the negative reputation South Africans had of us. As always, the existence of Nigerian criminals in the "other" country (doesn't matter what country) as proof that Nigerians were deservedly identified as criminals.